Finance sector development

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has just released a new policy paper on capital flows (IMF 2012). A recent editorial in the Financial Times describes it this way: As far as intellectual shifts go, the U-turn by the International Monetary Fund on capital controls is remarkable. In the 1990s, the IMF came close to including the promotion of capital account liberalisation in its rule book. On Monday, after a thorough three-year review, the fund has accepted institutionally that direct controls can play a useful role in calming volatile, international capital flows. (Financial Times. 3 December 2012)

Finance sector development

During the 2008 financial crisis, Asia experienced exchange rate volatility and liquidity shortages of the key currency—the US dollar—that severely affected trade within the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) region. The dollar is crucial to maintaining financial market stability at an appropriate liquidity level. While the dollar is expected to remain the key currency in the foreseeable future, the crisis has led to a rethinking of the global economy’s over-reliance on the dollar and its capital and financial markets, and the need to enhance the role of emerging currencies and their markets.

While it will take time for emerging market currencies to become significant reserve currencies, their growing importance in the settlement of cross-border trade and investment can no longer be ignored. Read more.

Environment

Urbanization degrades the environment, according to conventional wisdom. This view has led many developing countries to limit rural—urban migration and curb urban expansion. But this view is incorrect. There are a number of reasons urbanization can be good for the environment, if managed properly. First, urbanization brings higher productivity because of its positive externalities and economies of scale. Asian urban productivity is more than 5.5 times that of rural areas. The same output can be produced using fewer resources with urban agglomeration than without. In this sense, urbanization reduces the ecological footprint. The service sector requires urbanization because it needs a concentration of clients.

Regional cooperation and integration

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” said philosopher George Santayana. The aim of this paper is to draw lessons from Asia’s supposed “growth miracle” by disaggregating when, where—and why—growth occurred to better understand the roles of exogenous factors versus domestic policy choices. Our thesis is that the post-World War II “miracle” growth shared by many regional economies was a result of a unique set of circumstances linked not to their “Asian-ness”—but to exogenous, geo-political, developments and, in particular, to the Cold War. The Cold War was a battle for ideological leadership in political and economic domains between two nuclear powers who grew to accept a status quo based on the principle of mutual assured destruction (MAD).

Miscellaneous

The global economy is undergoing a fundamental change. Despite concerns over slowing growth in the People’s Republic of China, India, and Japan, and the possible dissolution of the eurozone, global economic growth is accelerating. How can this paradox be explained? If the global economy is shifting toward the more rapidly growing economies, then the world’s growth rate would shift toward the growth rates of the more rapidly growing economies. Thus, even if the growth rates of the PRC and India were to slow, global growth, which is considerably lower than that of both countries, would accelerate. The growth acceleration will lead to a new world economic order, associated with more rapidly growing countries such as the PRC and India, which are going to have a larger share of the global economy.

Social development and protection

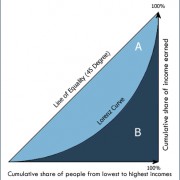

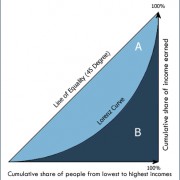

Developing Asia’s impressive growth continues, but faces a new challenge—inequality on the rise.1 Over the last few decades, the region has lifted people out of poverty at an unprecedented rate. But more recent experience contrasts with the “growth with equity” story that characterized the transformation of the newly industrialized economies in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 12 economies that account for more than four-fifths of the region’s population, income disparities expanded during the last two decades—despite the region’s world-beating performance in raising average incomes and reducing poverty.

Gender

In the next 50 years, most economic growth worldwide will take place outside the G7 countries. But that’s only half the story. Who are the people who will be the driving force for this growth? Many will be women. But too seldom conversations about economic growth turn a blind eye to gender issues, despite the fact that women comprise more than half of the global economy, 40% of the global workforce (Commonwealth Workforce Council), and $20+ trillion in financial spending worldwide (International Finance Corporation 2011). Women have a multiplier effect as consumers, building markets as they make the majority of purchase decisions in households. The question is not whether women will contribute to the future global economy but by how much – and where.

Regional cooperation and integration

ASEAN aims to create an ASEAN Economic Community by 2015, while the signing in May 2012 of a Trilateral Investment Agreement by the People’s Republic of China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea was a milestone in cooperation between three countries that together account for nearly 20% of global GDP and trade. The pact could lead to a three-way, free trade agreement (FTA) between the economic giants. Financial cooperation in ASEAN+3 has been accelerating. The region’s emergency financial safety net, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM), has doubled in size as decided by officials in May 2012, although it is yet to be made operational.

Governance and public sector management

Although it is widely considered to be an ineffective policy, a number of developing countries offer universal fuel subsidies. However, the prolonged implementation of fuel subsidies creates a misallocation of resources as a subsidy targets the fuel rather than the consumer. Consequently, fuel subsidies benefit the affluent more than the poor. A number of countries implement fuel subsidies, including Algeria, the People’s Republic of China, Ecuador, Egypt, Indonesia Iran, Iraq, Malaysia, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and Venezuela. Granado et al (2010) reported that in countries that have subsidized fuel, on average, the top income quintile consumed about six times more subsidized fuel than the bottom quintile.

Industry and trade

Deep free trade agreements (FTAs) are key to trade-led growth in Asia. Deep FTAs can support a comprehensive regional agenda for liberalization covering reductions in barriers to goods and services trade as well as opening new areas beyond the current purview of WTO negotiations (like investment, trade facilitation, competition, government procurement and intellectual property). Deep agreements can also help lock in structural reforms at national-level and promote implementation of second generation reforms. Accordingly, deep FTAs are useful for opening markets and removing obstacles to the spread of production networks throughout Asia and the Pacific. The depth of FTAs among Asia’s developing giants—the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India—is a topical issue.

Recent Comments