Women in rapidly urbanizing cities across South and Southeast Asia often face significant challenges in accessing public transportation. For many, this mobility challenge translates into daily struggles that impact their future opportunities and overall well-being. What is holding women back from using public transport, and how can governments break down these barriers?

The Mobility Dilemma: More Than Just Physical Movement

Mobility is about more than simply getting from point A to point B—it shapes how people engage with society and fully participate in the economy. For women, mobility is influenced by their dual roles in income-generating and caregiving activities, creating travel patterns that are often complex and multitasked, combining trips for work, childcare, and household management (Blumenberg 2009).

When women face restricted mobility, the impact reaches beyond physical movement, limiting access to essential services, employment, and education, and reducing their ability to participate fully in the economy and society. This not only affects quality of life and limits upward social mobility from an individual point of view but also results in untapped economic potential and reinforces social inequality from a societal perspective.

What Keeps Women from Using Public Transport?

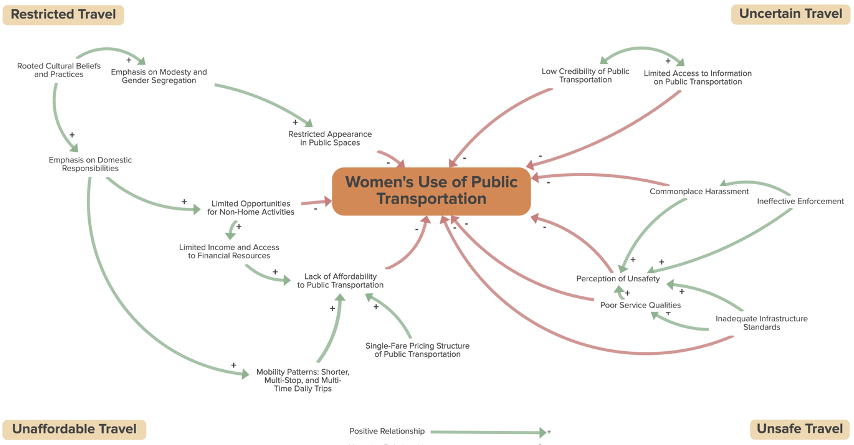

Understanding why women do not use public transport, either by choice or by circumstance, is essential to identifying actionable solutions. The reasons boil down to four main factors: uncertain travel, restricted travel, unaffordable travel, and unsafe travel. Indeed, each of these immediate barriers has underlying causes that speak to deeper structural problems.

Uncertain travel is a significant deterrent for women. Limited access to reliable information about public transportation routes, schedules, and fares often leaves them unaware of the available options (Blumenberg 2009). Even when such information is available, unpredictable transport schedules and inconsistent services in many parts of Asia make public transit less appealing for women managing time-sensitive tasks, such as childcare responsibilities.

Restricted travel is another critical issue rooted in entrenched cultural norms. Many societies in Asia emphasize the importance of women’s domestic, community, and familial responsibilities, limiting their opportunities to freely venture outside their homes (Adeel, Yeh, and Feng 2016). In some communities, these norms, rooted in ideas of modesty and gender segregation, restrict women’s presence in public spaces, including public transportation.

Affordability also poses a significant challenge. With limited economic opportunities and financial resources (Mason and Smith 2003), women often find public transport costs disproportionately burdensome. Their travel patterns, which typically involve shorter, multi-stop trips or traveling with children, differ from men’s but are rarely accounted for in transport pricing structures (Blumenberg 2009). Most systems rely on single-fare pricing, which fails to accommodate these unique needs, further exacerbating the unaffordability of public transit.

Finally, unsafe travel remains a persistent barrier. Inadequate infrastructure—such as poorly lit stops and unsafe pedestrian pathways—and poor service quality, including overcrowding and infrequent service, create an environment where women do not feel safe using public transport (Seedat, Mackenzie, and Mohan 2006). This is further aggravated by limited enforcement against gender-based violence, which contributes to commonplace harassment. Even where physical safety standards improve, the perception of risk persists, and many women continue to prefer door-to-door or private transport options for peace of mind.

The causal map in Figure 1 shows these factors and their relationships to women’s use of public transportation.

Figure 1: Causal Map of Factors Related to Women’s Use of Public Transportation

Note: This causal map includes only the main factors and primary relationships discussed in the article. It is intended as an overview and does not capture all nuances or additional factors that may influence women’s mobility challenges in public transportation.

How Can Gender-Sensitive Transport Policies Make a Difference?

While public transportation systems in developing Asia often fall short for women, change is possible with a gender-sensitive approach to transport policy.

Reliable Information and Smart Mobility Solutions

Access to reliable information is the first step to promoting the use of public transportation. There is strong demand for a centralized information platform with up-to-date and comprehensive details on travel, including information on options, routes, schedules, and fares. For this, a transport innovation, mobility-as-a-service (MaaS), a single and digitalized platform enabling multiple functions (information, ticketing, payment) while integrating multiple transport modes on a single platform, ensuring personalization and customization and mandating registration requirements, can be a potentially promising solution for policymakers to consider.

Safety-First Infrastructure and Service Upgrades

Women’s safety should be the top priority in urban transport planning. This means upgrading infrastructure through actions such as improving lighting at public transport stops and pedestrian pathways and installing surveillance cameras in critical areas. One practical example of gender-sensitive measures is the implementation of female-only carriages. In India, certain train carriages and sometimes entire trains are designated exclusively for female passengers to enhance their safety and comfort during travel. In addition to this, targeted staff training programs on how to handle harassment incidents, as well as more frequent patrolling and monitoring of public transit spaces, can also make journeys safer for women.

Empowerment of Women Within the Transport Sector

In the long run, increasing women’s representation in the transport workforce as operators and leaders can foster a more inclusive public transport environment. Government-led capacity-building and training programs offering scholarships and mentorship can encourage women to take on active roles in the transport industry.

A Gender-Sensitive Approach to Transport Policy

Ultimately, addressing women’s mobility challenges is about much more than improving transport options—it is a fundamental aspect of equitable development. When women are free to move, they are free to participate fully in society, improving their own quality of life, driving societal and economic growth, and contributing to building more equitable and sustainable cities. Policymakers across Asia should act now to build gender-sensitive public transportation systems that meet the needs of women and other vulnerable groups.

For meaningful progress, policymakers should base their strategies on robust, gender-disaggregated data. By building a comprehensive research database focused on women’s unique mobility needs across Asia, governments can create tailored, effective policies that drive the region closer to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

The authors wish to thank Radhika Behuria, Social and Gender Specialist (Consultant), Office of Market Development and PPPs, Asian Development Bank, for providing valuable comments on this article. They also acknowledge Hyunsuk Jung, Master’s Student, Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University, for his invaluable contributions to the causal map included in this article.

References

Adeel, M., A. Yeh, and Z. Feng. 2016. Gender Inequality in Mobility and Mode Choice in Pakistan. Transportation 44(6): 1519–1534.

Blumenberg, E. 2009. Moving in and Moving Around: Immigrants, Travel Behavior, and Implications for Transport Policy. Transportation Letters: The International Journal of Transportation Research 1(2): 169–180.

Chowdhury, S., and B. Van Wee. 2020. Examining Women’s Perception of Safety During Waiting Times at Public Transport Terminals. Transport Policy 94: 102–108.

Mason, K. O., and H. L. Smith. 2003. Women’s Empowerment and Social Context: Results from Five Asian Countries. Gender and Development Group, World Bank.

Seedat, M., S. Mackenzie, and D. Mohan. 2006. The Phenomenology of Being a Female Pedestrian in an African and an Asian City: A Qualitative Investigation. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 9(2): 139–153.

Uteng, T. P. 2009. Gender, Ethnicity, and Constrained Mobility: Insights into the Resultant Social Exclusion. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41(5): 1055–1071.

Comments are closed.