Among the many challenges facing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the coming decades, the most important is its need to massively expand its investment in education.

Among the many challenges facing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the coming decades, the most important is its need to massively expand its investment in education.

In an age of unprecedented levels of globalization, successful development has meant for the PRC, as for other countries, passing through three phases: Phase 1, joining the regional and global supply chains and production networks; Phase 2, imitating and adapting; Phase 3, innovating. These phases need not be mutually exclusive and may overlap.

The PRC today is just about completing Phase 1 and moving into Phase 2. The challenge for the next two to three decades will be for the country to complete Phase 2 successfully and move into Phase 3. However, moving up these rungs of the international income ladder will require vast amounts of investments in human capital, especially in education.

In successfully completing Phase 1, vast amounts of investments in human capital made by the PRC in pre-1978 years played a critical role. Without these investments, the process might well have stalled. The PRC’s continued economic success will depend on its ability to accumulate even greater amounts of new human capital.

In pursuing this path, the PRC can take strength from its own recent history of investment in human capital.

According to a study by Caselli et al. (2002), between the years 1950–1955 (base years) and 1970–1975 (end years), life expectancy in the PRC increased by over 22 years. This is a record that beats any other country during the same period and exceeds the next best performer by as many as 7 years, making the PRC a true outlier.

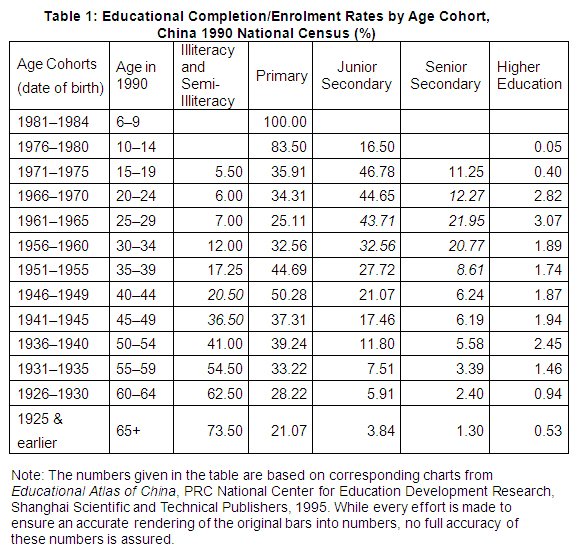

Furthermore, according to the 1990 PRC National Census findings (Table 1), illiteracy and semi-illiteracy among the under-30s and over-15s (i.e. those born between 1960 and 1975) fell to 6%, compared with 12% for the immediately preceding (older) age cohort 1956-1960 (by year of birth), and 17% for cohort 1951-55. Even more impressively, there was an eleven-percentage-point jump in junior secondary education completion rates between the two neighboring age cohorts, 1956-60 and 1961-65 (from 32.56% to 43.71%), and an even more dramatic twelve-percentage-point rise in senior secondary education completion rates from age cohorts 1951-55 to 1956-60 (from 8.61% to 20.77%). These dramatic rises were due to the spread of secondary education in the 1970s.

If the PRC is to overcome the danger of falling into the “middle-income trap” and to complete Phase 2 and to move into Phase 3, it needs to surpass the achievements of the pre-1978 reform years in education. In particular, it needs to improve and expand tertiary education.

Given the widely recognized imperfections in the market for education (principally capital market imperfections and externalities), direct public investments are required in this sector in addition to private investments. Such public investments may be channeled to the supply side (to increase educational facilities, provide more places for students, and improve the quality and relevance of education), and/or the demand side (to improve the population’s access to such education).

As in the past, efforts to improve the PRC’s education outcomes will face difficulties. The country’s drive to expand education experienced some setbacks in the early reform years. The same census data referred to above indicates that there was a sharp contraction in the senior secondary education completion rate of over nine percentage points between the age cohort 1961-65 and 1966-70 (from 21.95% to 12.27%). In subsequent reform years, efforts to expand and indeed universalize primary and junior secondary education were stepped up. However, there has been insufficient priority given to expanding and improving senior secondary and tertiary education, certainly not in terms of the resources allocated to it, especially from the public sector.

In the first decade of the current century, while college enrollment rates nearly tripled compared with the previous decade, to 23.3% in 2008, the expansion has mainly been financed through increased tuition fees. Total tuition fees for a four-year college degree and, before that, a three-year senior secondary qualification, now stand at around 60 times (college degree) and 20 times (senior secondary qualification) the annual per capita income of the poor (see Liu, et al 2006; Rozelle, 2010). As a result, most poor and low-income families were not able to afford this human capital investment for their children. Forced to rely principally on private investments, the expansion of the sector (especially in the case of tertiary education) has, by and large, failed to be accompanied by much-needed quality improvements, in the form of improved teaching, better facilities, and greater relevance of the education from the perspective of the changing market needs and economic environments of the country. In the absence of greater public investment in the sector, there is a question mark over whether there will be sufficient human capital stock over the next two to three decades and beyond to enable the PRC to move successfully through its imitation and adaption phase, and to the innovation phase. For the PRC to be able to do this, it must re-prioritize its policy and vastly expand its tertiary education by allocating adequate public resources to it.

In the long run, better and more widespread education, both general and tertiary, will promote social equity in the PRC as well. In general, the more educated a country’s population is, and the more widespread education is, particularly among the poor, the more equal the society tends to be in income and social conditions. So increased education and human capital investment should in the long run not only promote the level of the PRC’s economic and human development, but also improve on its social equity.

The PRC’s recent economic success has ridden on the tide of vast amounts of human capital investment made before 1978. Its continued economic success will depend on its ability to accumulate even greater amounts of new human capital. Indeed, from the human development viewpoint, health and education are not only a critical means of development, they are also part of the very aim of development.

_____

References:

Caselli, G., F. Meslé, and J.Vallin. 2002. Epidemiologic transition theory exceptions. Genus, 58: 9–52.

Liu. M. 2011. Understanding the Pattern of Growth and Equity in the People’s Republic of China. Working Paper 331. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Liu, M., J. Yu, and P. Li. 2006. Tuition fees and equitable access to higher education in China. Peking University Education Review, 4 (2): 47-61.

Rozelle, S., 2010. “China’s 12th 5 Year Plan Challenge: Building a Foundation for Long Term, Innovation-Based Growth and Equity.” Paper presented at NDRC-ADB International Seminar on China’s 12th Five Year Plan, Beijing, 19 January.

This article is based on the author’s earlier ADBI Working Paper 331 (Liu, 2011).

China’s billionaires should turn to philanthropy and invest in building schools and universities just as steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie gave most of his money to establish libraries, schools, and universities in the US, the UK, Canada and other countries.

I do agree very much with your analysis of the social investments made in the Communist period. Certainly many mistakes were made in the Mao period but progress was made too as you rightly point out.