SMEs and the Thai economy

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are significant contributors to economic activity and employment worldwide, and Thailand is no exception. In Thailand, SMEs represent the vast majority of firms and employ the bulk of the domestic workforce. According to the Office of SMEs Promotion (OSMEP 2019), in 2018, approximately 3 million companies were classed as SMEs in the country, comprising 99.8% of all companies. SMEs also accounted for 14 million jobs, or 86% of total employment.

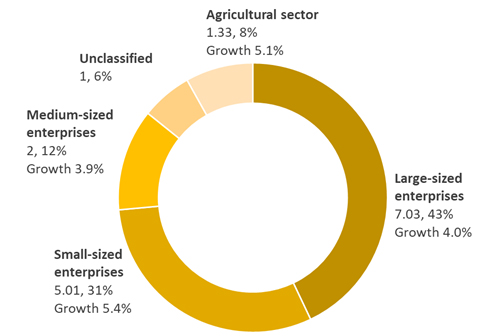

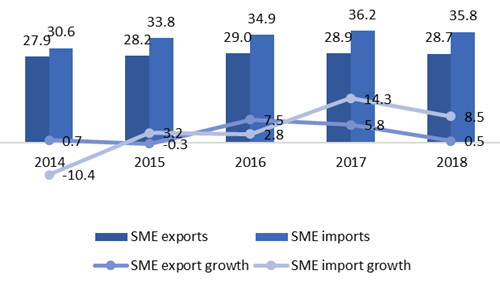

Although SMEs contribute as much as 45% (or $215 billion) to Thailand’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 1), their participation in international trade and global value chains (GVCs) remains limited. In 2018, the export volume of SMEs comprised only 29% (or $76 billion) of total exports and grew only 0.5% from the previous year (Figure 2). In contrast, large domestic firms and multinational enterprises dominate GVCs and therefore benefit greatly from the new opportunities that arise as a result of their participation.

Figure 1. Composition of Thailand’s GDP by Enterprise Size, 2018

(B trillion)

Source: Authors, adapted from OSMEP (2019).

Figure 2. Share of Thai SMEs in Exports and Imports and Expansion Rates, 2014‒2018(%)

SME = small and medium-sized enterprise.

Source: Authors, adapted from OSMEP (2019).

Opportunities and challenges of GVC participation

In a recent study, we show that SMEs in Thailand are involved less in both backward and forward GVC participation than larger firms (non-SMEs). In addition, GVC participation, both backward and forward, is positively associated with a firm’s performance. Our results therefore imply that being an SME is associated with a lower degree of GVC participation, but GVC participation can help firms (both SMEs and non-SMEs) increase their revenue. Moreover, a lower degree of GVC participation, especially in terms of backward GVC participation, implies that SMEs have a lower chance of upgrading their technology and products because of limited access to foreign high-quality inputs and technology. This becomes a vicious cycle since SMEs cannot participate in GVCs or move up value chains without upgrading their technology and products.

Taking the example of the Thai automotive and electronics industries, these two large industries are not listed among the top industries in terms of multiplier effect generation or the impact on other domestic industries (Korwatanasakul 2019). Moreover, local suppliers (usually SMEs) are mostly located in lower tiers of the production process since they do not have the sufficient technological capacity to meet global standards for the design and manufacture of modules for original equipment manufacturers. This is because industrial upgrading takes place mainly in multinational enterprises, and technology transfer from these suppliers is hardly observed. Only a few local suppliers under licensing agreements with global automakers can achieve the required technological sophistication and upgrade to higher tiers. In other words, local suppliers find it difficult to upgrade to higher tiers or higher positions in value chains and remain competitive without technological assistance from foreign companies (Korwatanasakul and Intarakumnerd 2020).

Policy priorities under COVID-19

Amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, both SMEs and large firms are experiencing disruptions in GVCs. However, SMEs are among the most vulnerable as they are relatively more labor-intensive and financially less liquid. SMEs are finding it more difficult than ever to participate in value chains. Moreover, although some SMEs are managing to engage or remain in GVCs, it is unlikely that they are fully benefiting from their participation under the current situation. According to Krung Thai Bank (2020), OSMEP reports that approximately 1.33 million SMEs, accounting for 44% of the GDP generated by SMEs, are affected by COVID-19, while 4 million people are at risk of being unemployed. If the situation is prolonged until the end of the year, SMEs are expected to lose more than $110 million in revenue, especially in the services sector. Hence, during the current crisis, policy priority should be given to immediately supporting and sustaining SMEs, such as through stimulus and relief packages. Nevertheless, providing short-term assistance to SMEs should not prevent the government from continuing to prompt SMEs to participate in value chains after domestic and global consumption recovers.

The government can empower SMEs through various policy tools, such as by promoting the digital capabilities of SMEs, easing access to commercial bank credit, offering corporate tax incentives, and providing high-quality business support services. Through these initiatives to raise SMEs’ productivity and financial liquidity, these firms will be able to engage in the upgrading of GVCs while becoming more resilient to future risks. In addition, the government may provide a platform for SMEs and all other stakeholders to mutually develop a national strategy for the post-pandemic recovery and a contingency plan to cope with the risk of disruptions in the future.

Read the working paper here.

_____

References:

Korwatanasakul, U. 2019. Global Value Chains in ASEAN: Thailand. Tokyo: ASEAN-Japan Centre.

Korwatanasakul, U. and Intarakumnerd, P. 2020. Global Value Chains in ASEAN: Automobiles. Tokyo: ASEAN-Japan Centre.

Korwatanasakul, U., and S. W. Paweenawat. 2020. Trade, Global Value Chains, and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Thailand: A Firm-Level Panel Analysis. ADBI Working Paper 1130. Tokyo: ADBI.

Krung Thai Bank. 2020. What Can SMEs Do to Deal with the Current Dull Situation? [SME จะทำอะไรได้บ้างในวันที่ทุกอย่างดูมืดมน] (in Thai). 402 (access: 16 May 2020).

Office of SMEs Promotion (OSMEP). 2019. SMEs White Paper Report 2018. Bangkok: OSMEP.

Comments are closed.