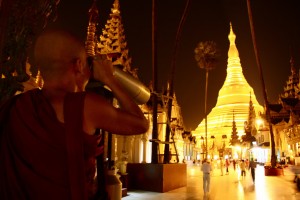

Photography by El-Branden Brazil

The remarkable, surprising, and extensive reformist policies of the new Republic of the Union of Myanmar have sparked interest throughout the international community. As one of the world’s last bastions of both relative isolation and new opportunities, Myanmar has recently become a magnet to which many are drawn.

Governments, international non-profit organizations, and businesses are exploring what they might do in a state marred by intense poverty but possessing abundant natural resources. With a literate and diverse population and a myriad of business opportunities, Myanmar entices with many diverse possibilities for rapid growth and social equity. Hotels are filling up with tourists who now feel more comfortable going to that once exotic land, and embassies may well expand staffs to handle more foreign assistance. Many more international NGOs will join the fifty or so already there, and those that are well established may increase staffs as needs become more visible and access increases. As sanctions against new investment seem likely to be relaxed, businessmen are seeking opportunities. The Burmese government will also have to gear up to meet its newly articulated social goals. All this has raised real estate prices to levels hitherto unknown. The pattern of outward migration by unemployed Burmese seeking work and education abroad may be reversed; instead, immigration into Myanmar by foreigners of many persuasions is expected.

How will all these new actors operate and flourish in an environment where it is the rare foreigner who has ever studied Burmese, a language with no useful cognates in the international arena, and where the competence in English, remarkably high two generations ago, has so drastically shrunk? They will draw upon the talents of those relatively sparse, well-educated, multi-lingual Burmese in the country. An educational system that has been underfunded, tightly controlled, poorly administered, and whose standards were once in the early post-colonial period the highest in the region, has sunk to the lowest ebb. The President of Myanmar has recognized the need for educational reforms.

The result of this influx is predictable, for it has been a pattern in other countries in foreign aid situations around the world for two generations. The prospect for positive change has been an elixir invigorating older programs and establishing new ones. When foreign assistance, public or private, pours into a country, and the government establishes new programs that are important, visible, and where opportunities for advancement are evident, the best and the brightest among the local population gravitate for employment to those indigenous and foreign groups. International public and private organizations usually offer higher salaries than local groups (and sometimes in foreign currency). Even state organizations may offer better pay as incentives to those who enroll in the new, prestigious and visible governmental departments, some of which are even encouraged or mandated by foreign aid institutions. Even if the pay is less than foreign groups might offer, the prospects for career advancement are better than in the traditional line ministries.

So, for a decade or more before educational institutions can catch up with the new demands for modernized skills, the attractions of the new opportunities may drain traditional ministries and government departments; even the staff of local non-governmental organizations may seek other work. In a real sense, then, as foreign assistance and businesses come in and operate, local governmental departments, organizations, and businesses may be diminished. Traditional ministries may lose whatever vigor they might once have had as good staffs seek opportunities elsewhere. The unsustainable equilibrium between the attractions of foreign organizations and the nationalistic and material benefits of working in indigenous settings sometimes take a considerable period to balance.

So as a result, progress on some areas may lead to atrophy in others. Intensive and broad in-country and external training is necessary to enable Myanmar to acquire the modern skills that are essential for the developmental path to which the government is committed. International bilateral, NGOs, and multilateral donors all should carefully calculate both the potential positive, and the risk of unintended negative, impacts of the early period of the openings. Foreign angels are needed, and may be going where before they indeed feared to tread, but they should be careful of where and how they step.

The migration of the best people from national institutions to better paid jobs in aid organizations does pose a problem for Burma as it emerges from its isolation. To attract and keep talented people the Burmese government will have to raise the pay and improve work conditions to compete with the NGOs.