The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Government of Japan are celebrating their 40th year of friendship and cooperation in 2013. A Commemorative Summit will be held in Tokyo starting on 13 December, at which leaders are expected to adopt a medium- to long-term vision to chart the future direction of ASEAN–Japan relations.

ASEAN and Japan’s cooperative partnership began in 1973 with the establishment of the ASEAN–Japan forum on synthetic rubber production issues. From this initial success, ASEAN and Japan have forged close cooperation through the years in the pursuit of peace, stability, development, and prosperity in Asia.

Japan’s Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, has visited all 10 ASEAN member states this year, starting soon after his assumption of office in late December 2012. This signifies the importance of ASEAN for Japan.

Japan wants to strengthen economic and political ties with ASEAN so that it can capture the region’s economic dynamism as part of its own growth strategy under so-called Abe-nomics. Abe-nomics focuses on aggressive monetary easing, flexible fiscal policy, and structural reforms for growth.

ASEAN is the third largest bloc in Asia in terms of population and GDP. It has a total of 617 million people, behind only the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India. Its GDP totals more than US$2.3 trillion, behind only the PRC and Japan. Although major economies in ASEAN were devastated by the 1997–1998 financial crisis, they have restored healthy economic growth and there has been a rapid rise in middle- and high-income households.

ASEAN is diverse in terms of race, religion, culture, levels of economic development, and political systems. It has, however, launched an initiative to create an ASEAN Community that comprises a Political and Security Community, an Economic Community, and a Social and Cultural Community. The reason for this initiative is that amid the rapid rise of the PRC and India in Asia, the only way for ASEAN to maintain peace and prosperity is to strengthen the internal coherence of ASEAN member states and, thus, create a united community. ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) building is particularly important as it aims to achieve deeper economic integration and greater international competitiveness, while maintaining ASEAN centrality in the regional cooperation architecture.

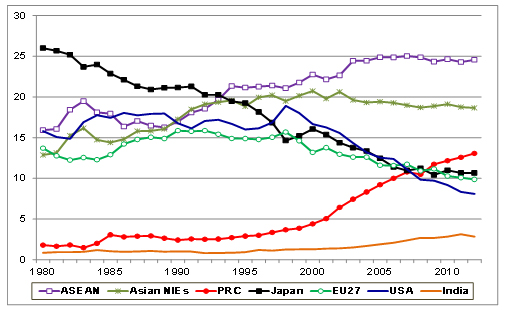

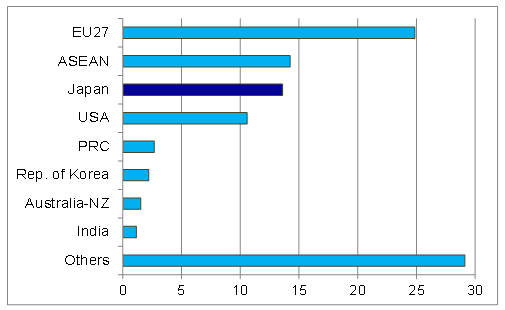

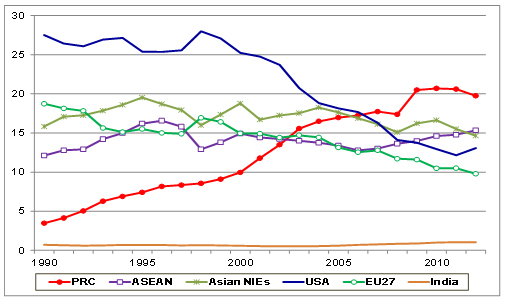

Japan is one of ASEAN’s oldest and most important dialogue partners and supporters. It is ASEAN’s second largest trade partner country with total bilateral trade amounting to US$263 billion in 2012 (see Figure 1).1 It is also among ASEAN’s largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) at US$122 billion in terms of FDI stock in 2012 (see Figure 2).2 ASEAN is the second largest trading partner for Japan, following the PRC (see Figure 3). For Japanese multinational corporations (MNCs), ASEAN countries collectively are their most important FDI destinations in Asia, ahead of the PRC (Figure 4). ASEAN offers an attractive market for Japanese firms providing goods and services, and a key production base for Japanese MNCs which have developed extensive production networks and supply chains throughout Asia.

Figure 1: Share of Trading Partners in ASEAN’s Total Trade (%)

Source: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics.

Note: Asian NIEs are the Asian newly industrialized economies, comprising Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China.

Figure 2: Share of FDI Source Countries/Regions in ASEAN’s Total FDI Inflows (% in the cumulative value during 1995–2012)

Source: ASEAN Secretariat.

Figure 3: Share of trading partners in Japan’s total trade (%)

Source: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics.

Note: Asian NIEs are the Asian newly industrialized economies, comprising Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China.

Figure 4: Share of Investment Destinations for Japan’s Outward FDI Stock (%)

Source: JETRO.

Note: Asian NIEs are the Asian newly industrialized economies, comprising Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China.

For example, Japanese automakers have established production bases for parts and components and final assembly in several ASEAN countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. In doing so, the automakers have taken into account the specific conditions of individual countries, such as the availability of trained workers, technological capabilities, the agglomeration of suppliers, infrastructure availability, market characteristics, and policy and tax incentives. These and other Japanese MNCs, including several small and medium-sized enterprises, have greatly contributed to the region’s economic development, technology transfer, and the de facto integration of ASEAN economies. The formation of an AEC would further improve the efficiency of regional production networks and supply chains.

Although ASEAN’s trade relationship with the PRC has expanded rapidly in recent years, the PRC’s presence as a source of FDI in ASEAN is still limited. Japan and ASEAN countries have nurtured friendly relationships and have no major historical issues or territorial disputes. ASEAN’s prosperity and stability are essential to the Japanese economy, and Japan can play a significant role for ASEAN’s economic development and regional integration to build an AEC by 2015 and beyond, especially through narrowing the development gap and enhancing ASEAN connectivity.

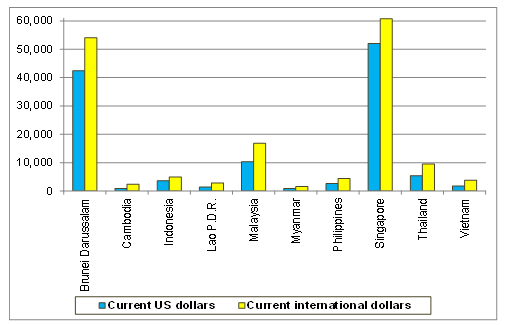

The development gap between ASEAN’s initial members and those which joined ASEAN in the second half of the 1990s—Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Viet Nam (the so-called CLMV countries)—is huge. For example, Singapore’s per capita GDP in 2012 was 60 times that of Myanmar, measured in current US dollars (Figure 5).3 While there has been a narrowing of the gap over time, more can be done and Japan can help in this. Japan’s support for human resource development, agricultural sector development, infrastructure building, and expansion of supply chains to the CLMV countries would be vital.

Figure 5: Per Capita GDP of ASEAN Member States (dollars), 2012

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook database, October 2013.

Japan has been the largest contributor to the Initiative for ASEAN Integration—a program dedicated to narrowing income gaps in CLMV. A narrower development gap would be essential to deepening the AEC and to the successful conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership for wider free trade and investment liberalization, which is currently being negotiated by the ASEAN+6 countries.

In the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan, yet another severe natural disaster to strike Asia in recent years, Japan can provide disaster risk management (DRM) support for ASEAN. This may include support for constructing preventive infrastructure facilities, organizing regular policy dialogues among the region’s DRM authorities, and enhancing human and technical capacity for DRM.

Japan can also provide support for the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, including cross-border infrastructure development and trade facilitation such as smoothing customs procedures. One way would be to connect the Greater Mekong Subregion and South Asia through cross-border infrastructure such as highways, railways, maritime, and power transmission. This would require substantial infrastructure investment in the transport system (including roads, ports, and railways) and the power sector inside Myanmar as well as cross-border infrastructure investment projects connecting Myanmar with Thailand, the rest of the CLMV, and India.

Improving regional infrastructure would boost the competitiveness of CLMV countries which would help them to be more connected with each other, with other ASEAN countries, and with South Asian economies, particularly India. Infrastructure projects linking remote islands in Indonesia and the Philippines with economic centers would also greatly help economic development in archipelagic ASEAN.

ASEAN countries’ response to the global financial crisis has shown the region’s macroeconomic resilience, which has been built up during the last 15 years to strengthen regional macroeconomic and financial conditions. Nonetheless, external financial volatility could affect ASEAN countries. Thus, another area in which Japan could provide big support would be the expansion or introduction of bilateral currency swap arrangements so that short-term US dollar liquidity can be made available in the event of financial and currency crises, including for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Such bilateral currency swap arrangements would complement the existing multilateralized Chiang Mai Initiative.

Japan can also continue to play a crucial role in the development of regional bond markets through the Asian Bond Markets Initiative, Credit Guarantee and Investment Facility, and Japan–ASEAN Technical Assistance Fund for bond market development. These initiatives and programs can support the rapid, sustainable, and inclusive growth of ASEAN economies.

The Asian Development Bank Institute is about to publish a study on ASEAN economies, in which it identifies the potential for the region to reach a quality of life similar to that enjoyed by countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development today. This bright future for the region depends on their determination to proceed with structural reforms and more initiatives for regional integration, toward the creation of a borderless economic community by 2030. Japan has a large role to play in assisting ASEAN members achieve their aspirations.

_____

1 If the ASEAN economies and the Asian newly industrialized economies (NIEs comprising Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Singapore; and Taipei,China) are respectively grouped together, Japan is the fourth largest trading partner for ASEAN, following ASEAN, the Asian NIEs, and the PRC.

2 If the EU and the ASEAN economies are respectively grouped together, Japan is the third largest source of FDI for ASEAN, following EU and ASEAN, measured by the cumulative value of FDI inflows to ASEAN during 1995–2012. However, the OECD data for FDI stock in ASEAN for 2011 show that Japan’s FDI stock in ASEAN was the second largest (at US$111 billion) only behind the US (US$160 billion) but ahead of the whole of the EU (US$106 billion).

3 Based on current international dollars, the per capita GDP gap between Singapore and Myanmar was 38 times in 2012. In 1998, per capita GDP of Singapore was 140 times (measured in current US dollars) and 67 times (measured in current international dollars) that of Myanmar. Thus there has been improvement in narrowing the gap as a trend.

Comments are closed.