Children may learn better when taught in their mother tongue—an idea that has fueled the mother tongue-based education movement. Within the education system, the language of instruction influences children’s ability to study, interact, and convey ideas, ultimately shaping learning outcomes. According to the World Bank [1], implementing mother tongue-based education is “cost-effective and simpler to organize than usually thought.” This approach has gained support from policymakers, civil society, and agencies like UNESCO, aligning with efforts to address global learning crises and preserve endangered local languages.

The movement has also found support in empirical studies demonstrating that mother tongue-based education effectively enhances learning outcomes. However, these studies face a notable limitation: they primarily focus on countries with relatively low linguistic diversity. In such contexts, the language of instruction is often selected from the majority language or implemented using two or three mother tongues. In contrast, developing countries in Asia, where improving learning outcomes remains challenging, face the challenge of managing higher linguistic diversity [2]. The evidence regarding the effectiveness of mother tongue-based education in such diverse societies remains inconclusive.

In a new paper [3] published in Labour Economics in December 2024, we evaluate the Philippines’ experience with its Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) policy. The findings highlight the adverse effect of mother tongue-based education in diverse contexts, where implementation faces inherently complex challenges.

Language in Education Policy in the Philippines

In 2013, the Philippines implemented the nationwide MTB-MLE policy to scale up mother tongue education in early grades (kindergarten to grade 3). The country is home to many ethnolinguistic groups, with over 180 languages spoken by more than 117 million people across the archipelago. It has a linguistic fractionalization of 0.85, indicating that there is an 85% chance that two randomly sampled Filipinos have different mother tongues. This setting provides an opportunity to study the effects of mother tongue-based education in a highly diverse society.

After several pilot programs in a small number of schools, the government mandated nationwide implementation of MTB-MLE. The policy had two main objectives of requiring the use of the mother tongue as the language of instruction from kindergarten to grade 3, and introducing the mother tongue as a new subject area. The initial implementation covered 12 mother tongues, later expanded to 19. The policy was made compulsory for all public schools under the 2013 Enhanced Basic Education Act.

Lessons Learned from MTB-MLE

On paper, changing policy on the language of instruction to boost learning outcomes may appear simple and cost-effective. The change significantly reduced linguistic distance—a measure of how different the language used in a school is from a student’s mother tongue—by about 43%–76%. Before the adoption of the policy, students in grades 1–3 were taught in English and Filipino. Under MTB-MLE, they are taught in one of 19 local languages, which are generally closer to their native language.

Nevertheless, implementation is complex. On the one hand, a school survey reported that compliance is high [4] since approximately 99.5% of public schools and 88% of private schools implemented the policy. On the other hand, while the government led in contextualizing textbooks, providing teacher training, and introducing a new national assessment for grade 3 students in the newly adopted languages, numerous studies have reported significant challenges in implementation due to the inadequacy of these materials and training.

Significant challenges were also noted at the school level, especially during the initial stages of implementation. For instance, data on students’ linguistic backgrounds may have existed but were not readily usable for policy implementation. Ideally, the language of instruction should meet the language needs of all students in a class, or the second-best option is to employ the language with the minimum linguistic distance for them. Assuming the adoption of this second-best option, MTB-MLE coverage stayed at around 60% of the population, with significant diversity across regions.

Impact of the MTB-MLE Policy on Learning Outcomes

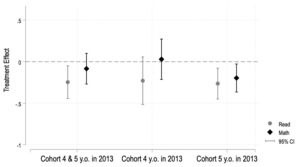

The implementation challenges of MTB-MLE prevented the Philippines from reaping learning gains in mathematics and reading. Evidence shows that students performed worse after the policy’s implementation. Using a national household-based survey conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority, a rigorous evaluation shows that the MTB-MLE policy reduced foundational reading ability [5] (i.e., reading simple text and extracting the information) by approximately 2.1–2.3 percentage points, comparable to nearly a full year of schooling in the Philippines. These effects were measured only for student cohorts fully exposed to the policy over 3 years, from the start of schooling through to K3, during the initial implementation phase. Foundational mathematics skills, such as the ability to solve simple arithmetic problems, also suffered, though this effect was limited to the first cohort of students exposed to the policy.

Figure 1. Impact of MTB-MLE on Reading and Mathematics Skills

Several factors may intensify the negative impact of MTB-MLE. Limited school facilities, resources, and capacity pose significant challenges to the effective implementation of the policy. Consequently, the impact is likely to vary between urban and rural areas, given their differing levels of resources and capacity to execute the policy. As anticipated, the adverse effects are more pronounced in rural areas. In urban areas, where resources and school capacity are generally more robust, MTB-MLE similarly fails to enhance learning outcomes. Initially, MTB-MLE was thought to be easier to implement in contexts with lower linguistic complexity. However, no evidence suggests that the effects differ statistically between regions with low and high linguistic diversity.

Additionally, the MTB-MLE policy is expected to have varying effects based on household and individual characteristics, such as gender, wealth status, and parental education. For instance, the policy impacts girls and boys differently, with a notably negative and significant effect observed for girls. However, in the context of the Philippines, this disparity may not exacerbate the existing gender gap in educational outcomes, as girls in grade 5 already demonstrate slightly higher proficiency in foundational skills compared to boys.

Policy Implications

Policymakers must consider the inherent implementation challenges of mother tongue-based education in a multilingual context. Designing such policy for diverse countries is logistically complex, as populations often speak distinct languages while coexisting in the same area. Ultimately, the shift from a bilingual education system to MTB-MLE in the Philippines, a highly diverse multilingual context, represents a transition to monolingual education using multiple mother tongues. The same challenge will be faced in other linguistically diverse situations in other countries.

Countries must either allocate sufficient resources for thorough preparation before implementing such policies or consider alternative strategies to enhance learning outcomes. Adequate planning, including teacher training, material development, and stakeholder engagement, is critical to ensure success. Without these foundational steps, even well-intentioned reforms may struggle to achieve their intended impact.

Finally, policymakers should not underestimate the costs of such complex policies while overestimating their benefits for the education system. While the advantages of mother tongue-based education remain questionable for diverse countries like the Philippines, it is more likely to inflict financial, logistical, and social costs.