Informal employment encompasses workers who are not effectively covered by formal arrangements, such as commercial laws, reporting procedures for economic activities, income taxation, labor legislation, or social security laws. This lack of coverage leaves them exposed to economic and personal risks (ILO STAT 2023, ILO 2023a, 2023b, 2024a, 2024b; DW4SD Resource Platform 2002). In developing countries, a substantial portion of employment and output generation is concentrated in the informal sector, contributing significantly to gross domestic product (Schneider et al. 2010).

Globally, the informal sector comprises over half of the labor force. Over 90% of micro and small enterprises (MSEs) worldwide operate within the informal economy, including 80%–90% in South Asia. Informal work is closely tied to gender inequality, with women in low- and lower-middle-income countries more likely than men to hold precarious and low-paying informal employment positions. Although the size of the informal sector tends to decrease as economies develop, significant variations exist across regions and countries.

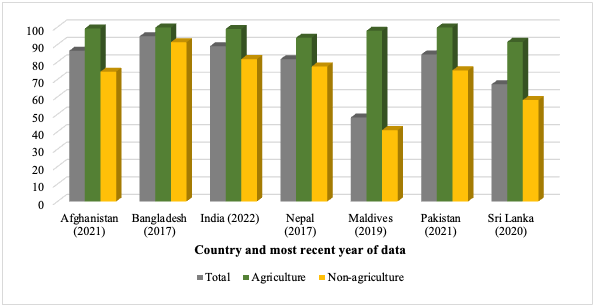

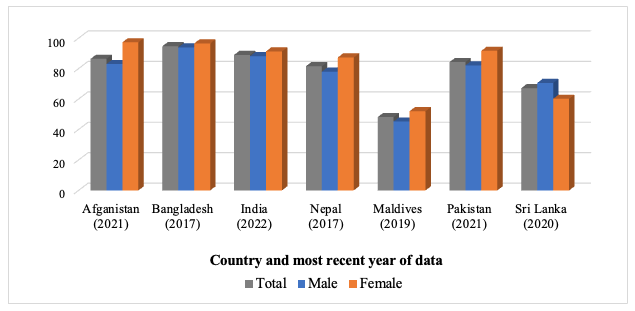

The high prevalence of informal labor, especially in emerging markets and developing economies, increasingly poses a barrier to sustainable development. Informal workers are more likely to experience poverty than formal workers due to the absence of formal contracts and social protection and lower educational levels. In South Asia, the agricultural sector has a relatively higher proportion of informal workers than the non-agricultural sector. Female participation in the informal economy is generally higher, except in Maldives and Sri Lanka, where it is considerably lower (Department of Census and Statistics 2022).

Efforts and Challenges Faced by the Informal Labor Market

South Asian countries have implemented various social security and welfare policies to support informal workers, underscoring the importance of these measures in enhancing livelihoods and reducing vulnerability. Bangladesh’s National Social Security Strategy aims to extend coverage to all citizens, focusing on vulnerable groups and includes health insurance, social safety net programs, and extensive skills training initiatives. India offers health insurance through Ayushman Bharat, guarantees rural employment via the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, and provides pension schemes like the National Pension Scheme and Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-Dhan for informal workers. The Maldives’ social protection system includes cash transfers, food assistance, a national health insurance scheme (Aasandha), and pension schemes for older citizens. Nepal’s Social Security Fund and National Health Insurance Program aim to extend benefits to informal workers, supported by employment support programs. Sri Lanka’s Samurdhi Programme provides financial aid and social welfare services to low-income households, including informal workers. Despite these efforts, challenges remain in ensuring adequate coverage, effectiveness, and accessibility of these programs, particularly for the most vulnerable segments of the informal economy.

Informal workers are found in agriculture and non-agricultural sectors and include small enterprises, private work, household projects, and community services. Agriculture and female workers are the most prevalent within these categories, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. Agricultural workers and women are particularly vulnerable due to income inequality, seasonal instability and temporary work, fluctuations in harvests, and market prices.

Figure 1: Proportion of Informal Employment in Total Employment by Sector (%)

Source: ILO STAT (2023).

Figure 2: Proportion of Informal Employment in Total Employment by Gender (%)

Source: ILO STAT (2023).

Recent digitalization has revolutionized traditional work frameworks, leading to the categorization of workers into digital platform workers (platform workers) and traditional workers (non-platform workers) (Abraham et al. 2019). Despite this shift, the social protection issues for these workers remain the same. Both platform and non-platform workers face challenges such as a lack of fixed wages, ongoing contracts, and predictable earnings (Datta et al. 2023).

Expanding social safety nets alone is insufficient to support all workers in the informal economy, especially in urban and agricultural sectors in rural areas. There is a need for economic inclusion programs and productivity-enhancing measures, particularly for women, girls, and youth, to effectively address these social protection issues. The unique challenges faced by these groups are hazardous work environments, long hours, and climate change, which further exacerbate this vulnerability. Engaging in informal employment increases the risk of income insecurity, poor occupational safety and health, challenging working conditions, and lack of support for retirement, old age, disaster resilience, education, and legal aid (Lund 2012; Mahmood 2010; Mishra 2017; Rajan 2002; Sharma 2013; Unni and Rani 2003).

Country-specific characteristics and institutions influence the size of the informal sector, making it clear that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 aims to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work. To achieve this, target 8.3 calls for policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity, innovation, and the formalization and expansion of MSEs by enhancing access to financial services (United Nations, 2024). These changing work landscapes due to digital advancements and significant social security and welfare policy implementations offer hope for accommodating the evolving nature of work from traditional to platform-based.

Policy Recommendations

Education reforms should guarantee equal access for everyone and offer ample technical and vocational training opportunities. These steps are essential for providing individuals with the skills necessary to transition to employment on digital platforms. Integrating the entire informal sector into the digital network makes it easier for the government to track and reduce informality.

The tax system design should not unintentionally create more reasons for individuals and businesses to stay in the informal sector. This can be achieved by reducing tax rates, minimizing payroll taxes, and implementing supportive social protection measures to support the most vulnerable.

Financial inclusion is necessary, and the government should expand access to financial services and remove key constraints for informal firms and finance entrepreneurs by providing digital financial services, such as mobile financial services, to all individuals. Digital platforms, including government-to-person mobile transfers, can contribute to inclusive growth by providing financial accounts to the unbanked, empowering women financially, and helping small and medium-sized enterprises grow within the formal sector.

Finally, social security is not just about financial stability in old age. It is about recognizing and supporting the contributions of all workers, regardless of their employment status. By establishing a universal pension scheme, introducing affordable health insurance, and strengthening education and unemployment programs, informal workers can benefit from essential coverage and support. Together, these measures are not just recommendations but are a necessity for a more inclusive and supportive economy.

References

Abraham, K. G., J. Haltiwanger, K. Sandusky, and J. Spletzer. 2019. The Rise of the Gig Economy: Fact or Fiction? AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191039

Datta, N., C. Rong, S. Singh, C. Stinshoff, N. Iacob, N. S. Nigatu, M. Nxumalo, and L. Klimaviciute. 2023. Working Without Borders: The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work. World Bank.

Decent Work for Sustainable Development (DW4SD) Resource Platform. 2002. The General Conference of the International Labour Organization, Meeting in Its 90th Session. 2002. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/—reloff/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_080105.pdf

Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2022. Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey: Annual Report. Department of Census and Statistics. http://www.statistics.gov.lk/LabourForce/StaticalInformation/AnnualReports/2022

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2023a. Extending Contribution-Based Social Security Schemes for Workers in the Informal Economy and Self-Employed in Nepal. ILO. https://webapps.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-kathmandu/documents/publication/wcms_869013.pdf

ILO. 2023b. Informal Economy in South Asia. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/newdelhi/areasofwork/informal-economy/lang–en/index.htm

ILO. 2024a. Way Out of Informality: Facilitating Formalisation of Informal Economy in South Asia. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/dhaka/Whatwedo/Projects/WCMS_215714/lang–en/index.htm

ILO. 2024b. Informal Economy. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/dw4sd/themes/informal-economy/lang–en/index.htm

ILO STAT. 2023. Statistics on the Informal Economy. ILO. https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/informality/

Lund, F. 2012. Work-Related Social Protection for Informal Workers. International Social Security Review 65(4): 9–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-246X.2012.01445.x

Mahmood, S. A. 2010. Social Security Schemes for the Unorganized Sector in India: A Critical Analysis. Management and Labour Studies 35(1): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042×1003500108

Mishra, S. 2017. Social Security for Unorganised Workers in India. Journal of Social Sciences 53(2): 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2017.1340114

Rajan, S. I. 2002. Social Security for the Unorganized Sector in South Asia. International Social Security Review 55(4): 143–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246X.00143

Schneider, F., A. Buehn, and C. E. Montenegro. 2010. New Estimates for the Shadow Economies All Over the World. International Economic Journal 24(4): 443–461.

Sharma, A. N. 2013. Towards Universalising Social Protection for Informal Workers. Indian Journal of Human Development 7(2): 356–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973703020130218

United Nations. 2024. SDG Indicators: Metadata Repository. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=8&Target=8.3

Unni, J., and U. Rani. 2003. Social Protection for Informal Workers in India: Insecurities, Instruments and Institutional Mechanisms. Development and Change 34(1): 127–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00299

Comments are closed.