The Indian state of Haryana sets an outstanding example in addressing groundwater depletion and can provide valuable insights for tackling the groundwater crisis in South Asia. The state’s well-planned approach includes data-driven cultivated crop management, direct cash transfers, incentives for purchasing equipment, and consistent government engagement and interactions with farmers, which have led to a notable improvement in groundwater levels.

Currently, South Asian countries are grappling with severe groundwater depletion, with agricultural groundwater withdrawal reaching 91%, surpassing the global average of 71% (FAO 2022). High population density coupled with water-intensive farming practices, especially traditional rice cultivation (TRC), are the region’s leading causes of groundwater depletion (Nawaz et al. 2019). TRC requires high amounts of water, ranging from 800 liters to 5,000 liters, to produce just 1 kilogram of rice (Bouman 2023). Besides, TRC, tillage methods lead to decreasing soil organic matter (Alam et al. 2014), and transplanting requires approximately 250–300 person-hours per hectare (Singh et al. 1985). Consequently, it is no longer a sustainable option for the state to produce food grains.

In this context, mechanical transplanting and direct seeding of rice are the two primary options available. However, mechanical transplanting is challenging due to the technical requirements of establishing mat-type nurseries and operating transplanting machinery (Kumar et al. 2011). As a result, direct-seeded rice (DSR) is a practical choice, although it still has certain limitations.

What is the DSR technique?

DSR is a crop cultivation system wherein rice seeds are sown directly into the field instead of the traditional method of growing seedlings in a nursery and then transplanting them into flooded fields. The method reduces labor, minimizes drudgery, shortens cultivation time, and demands less water by eliminating the need for seedling, uprooting, and transplanting (Kumar et al., 2011). Additionally, DSR contributes to lower greenhouse gas emissions, benefiting the environment, and increasing farmers’ total income by reducing cultivation costs (Alam et al., 2014).

Why is DSR adoption low in South Asia?

Although the benefits of DSR are evident, the transition from TRC to DSR faces several obstacles, resulting in low adoption rates in South Asia. One major challenge is the low purchasing power of farmers because of market inefficiency, which compels farmers to adopt traditional ways of cultivation (Farooq et al. 2011). Additionally, the exposure of DSR seeds to birds and pests increases the risk of seed loss, further discouraging farmers from adopting the technique (Kaur et al. 2017). Effective weed management in DSR also proves challenging, requiring specific knowledge and resources that may not be readily accessible, especially to small farmers (Kumar et al. 2011).

Direct cash transfer and incentives to farmers for increasing the adoption of direct seeded rice: The success story of Haryana

Haryana faces severe challenges of falling groundwater tables as annual groundwater withdrawal in Haryana amounts to 134.14 % of its extractable groundwater resources (Central Ground Water Board of India 2022). A report published by the Central Ground Water Board of India (2019) revealed that 19 of the state’s administrative blocks are facing a groundwater crisis, falling below 40 meters. However, the state government implemented a concrete plan to tackle the groundwater crisis by adopting the DSR technique.

On 5 July 2019, the Haryana government launched the online portal, Meri Fasal Mera Byora (My Crops My Details). By uploading information about cultivated crops and bank account details to the portal, farmers can become eligible to participate in various government schemes after verification by the relevant department. To encourage farmers to upload details about their cultivated crops, the government incentivizes ₹10 per acre to farmers and ₹5 per entry to Common Service Centres (village-level e-services centers). Over 900,000 farmers regularly upload information about cultivated crops to the portal, making it easier for the government to implement farmer-friendly initiatives. For instance, on 6 May 2020, the Haryana government launched a water conservation scheme for the 19 administrative blocks called Mera Pani Meri Virasat (My Water My Assets). Under this scheme, farmers who cultivated crops other than rice received a direct cash transfer of ₹7,000 per acre. Consequently, in 2020, rice cultivation decreased by 96,000 acres (Department of Agriculture Government of Haryana 2021).

In 2021, the government announced a direct cash transfer of ₹5,000 per acre (maximum 2.5 acres) to encourage rice cultivation using the DSR technique. Additionally, a subsidy of ₹40,000 was offered to purchase zero-tillage direct-seeded rice machines (Department of Agriculture, Government of Haryana 2021). These incentives induced farmers to adopt the DSR technique on 17,444 acres, just slightly below the target of 20,000. Encouraged by the positive response from farmers, the government set a target of sowing rice using the DSR technique on 0.1 million acres in 12 blocks for 2022. However, during this phase, there was no such limit of 2.5 acres, and farmers could cultivate rice using the DSR technique on more than 2.5 acres. As per the data, 16,641 verified cultivators in Haryana grew rice on 72,900 acres using the DSR technique, saving 315 billion liters of water (Department of Agriculture, Government of Haryana, 2022). After field inspections, the government released over ₹290 million as incentives directly to farmers’ bank accounts.

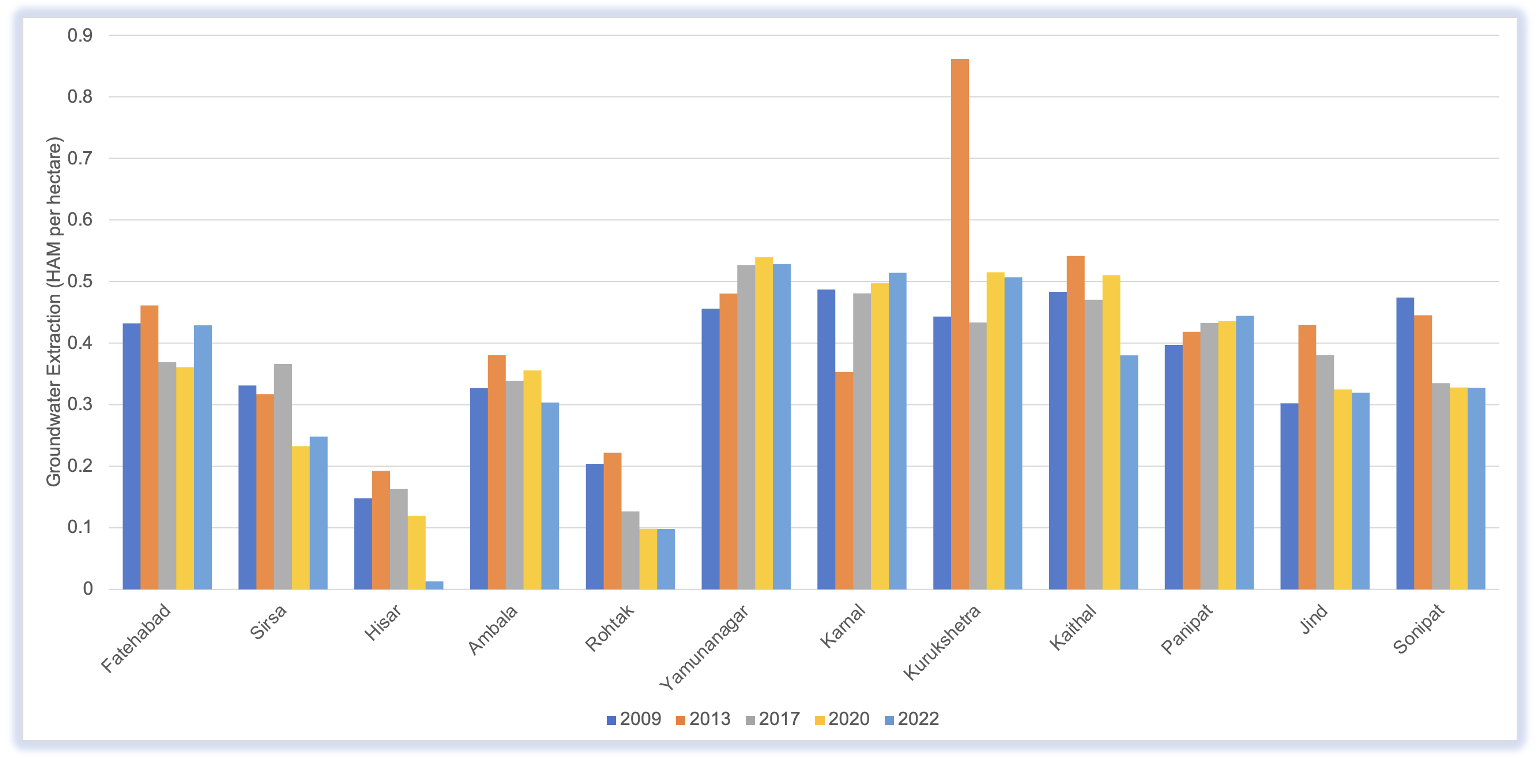

Continuing their efforts, the state government allocated ₹810 million for 2023 to promote DSR. As a result, the response has been outstanding, with 44,309 farmers adopting the DSR technique on 311,365 acres by 21 June 2023, surpassing the target of 225,000 acres. The Chief Minister of Haryana regularly holds meetings with farmers in rice-dominated districts, motivating them to adopt alternative crops or practices. Farmers who have responded to water conservation schemes are honored with the title of “Amrit Krantikari Mitra” (revolutionary angel friends). The data reveal that in a span of just 2 years, water extraction decreased in 7 districts out of 12 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: District-Wise Groundwater Extraction from 2009 to 2022

Source: Central Ground Water Board (2022).

Lessons for South Asian countries

Haryana’s experience with DSR adoption can serve as a valuable case study for other South Asian countries. Promoting DSR adoption with data-driven crop cultivation management, direct cash transfers, incentives for machine purchase, and the government’s dedicated interaction with farmers can serve as a blueprint for other South Asian countries dealing with similar groundwater challenges.

In addition, it is essential to establish platforms for regional cooperation, knowledge exchange, and collaboration to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and best practices. Countries must also assess their specific contexts, including agro-climatic and socioeconomic conditions, as well as policy frameworks, to determine the feasibility and applicability of adopting the DSR technique or similar water-saving practices. Local adaptation and contextualization are crucial for successful implementation.

References

Alam, M. K., M. M. Islam, N. Salahin, and M. Hasanuzzaman, M. 2014. Effect of Tillage Practices on Soil Properties and Crop Productivity in Wheat-Mungbean-Rice Cropping System Under Subtropical Climatic Conditions. The Scientific World Journal.

Bouman, B. A. M. 2003. Examining the Water-Shortage Problem in Rice Systems: Water-Saving Irrigation Technologies. In Rice Science: Innovations and Impact for Livelihood. Proceedings of the International Rice Research Conference, Beijing, China, 16-19 September 2002 (pp. 519–535). International Rice Research Institute.

Central Ground Water Board of India. 2019. Ground Water Year Book of Haryana State (2019-2019).

Central Ground Water Board of India. 2022. Dynamic Ground Water Resources of India. North West Zone Chandigarh, and Ground Water Cell, Irrigation and Water Resources Department, Haryana.

Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Haryana. 2021. https://agriharyana.gov.in/mechschemes

Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Haryana. 2022. https://agriharyana.gov.in/data/Schemes/News%20Advertise%20final.pdf

FAO Statistics. 2022. Statistical Yearbook: World Food and Agriculture 2022. FAO.

Farooq, M. K. H. M., K. H. Siddique, H. Rehman, T. Aziz, D. J. Lee, and A. Wahid. 2011. Rice Direct Seeding: Experiences, Challenges and Opportunities. Soil and Tillage Research 111(2): 87–98https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2010.10.008

Kaur, J., and A. Singh. 2017. Direct Seeded Rice: Prospects, Problems/Constraints and Researchable Issues in India. Current Agriculture Research Journal 5(1): 13–32.

Kumar, V. and J. K. Ladha. 2011. Direct Seeding of Rice: Recent Developments and Future Research Needs. Advances in Agronomy 111: 297–413.

Nawaz, A., M. Farooq, F. Nadeem, K. H. Siddique, and R. Lal. 2019. Rice–Wheat Cropping Systems in South Asia: Issues, Options and Opportunities. Crop and Pasture Science 70(5): 395–427.

Singh, G., T. R. Sharma, and C. W. Bockhop. 1985. Field Performance Evaluation of a Manual Rice Transplanter. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 32(3): 259–268.

Comments are closed.