A lack of legal advice during a project’s procurement process can result in unclear contractual terms that undermine the project and lead to costly and lengthy dispute resolution processes. This is particularly relevant in the context of large infrastructure projects given the multiplicity of stakeholders, the technical complexities of risk allocation and budget decisions, and the largely negative repercussions of timeline overruns. For instance, due to a lack of attentive legal advice during the contract drafting stage of the Neijiang 207 Provincial Highway in the People’s Republic of China, important clauses were omitted from the contract, resulting in court proceedings that delayed the project and increased costs (Zheng et al. 2021).

FIDIC contracts are standardized, globally accepted construction contracts issued by the International Federation of Consulting Engineers.1 International aid institutions such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and Japan International Cooperation Agency make use of these contracts for large infrastructure project grants for developing countries. They are used for two main reasons: familiarity and precedent. The widespread use of these contracts ensures practitioners are familiar with the terms, which facilitates the implementation of the contract. Furthermore, prior advice or judgements regarding a FIDIC contract remain applicable to subsequent contracts—a principle referred to as precedent—which provides clients with a degree of certainty in the outcome, also facilitating contract implementation. In general, the contracts can be considered “contracts by engineers for engineers” and, thanks to familiarity and precedent, they reduce the need for legal aid or advice during the procurement process of public–private partnerships (Søresen 2022).

In addition, a lack of legal advice precludes the possibility of making FIDIC contracts flexible to local standards. In certain situations, a lack of flexibility can force practitioners to largely deviate from the FIDIC golden principles,2 which makes said contracts lose their familiarity and precedent advantages.

Responding to an appeal by Task Group 15 (mandated with determining the limits of acceptable modifications to FIDIC clauses so that resulting contracts can still be qualified as FIDIC) and FIDIC for measures to prevent or limit misuses of FIDIC conditions of contract, we discuss the benefits of seeking legal advice from the early stages of the procurement process, with a focus on legal advice for contract drafting and lawyers’ participation in dispute boards.

Lawyers’ participation in contract preparation can make FIDIC contract terms clearer. A survey by the NEC (2014) highlights how practitioners can find FIDIC contracts to have limited clarity on points of accountability, risk allocation, the definition of roles, dispute resolution, and procedures for evaluating and coping with change. The general phrasing may be difficult for practitioners to understand due to large portions of cross-referencing articles and long sentences (NEC, 2014). But issues with FIDIC expand beyond the contractual text. In a presentation of case studies of using FIDIC in Southeast Asia, Castro (2013) points out how clashes with national laws, lack of knowledge on FIDIC, and different interpretations or implications of the terms of a contract—for instance, notices that are considered hostile, leading to strained relationships—can be additional causes of the unsuccessful implementation or drafting of FIDIC contracts.

Lawyers can aid in both in-text clarity and cultural issues. First, a legal review of the text allows clients to receive clarification on roles, dispute resolution clauses, timelines for implementation, and risk allocation, therefore solving the clarity issues of FIDIC contracts. Second, lawyers can bridge the gap between FIDIC terms and national law, given their knowledge of both, and advocate for FIDIC. This further increases the practitioner’s knowledge and, in turn, the comfortability of working under FIDIC. Within the context of cultural differences, local lawyers can also aid in the appropriate translation of contractual terms to avoid unintended implications of the wording used in a contract. On average (globally), the cost of a project legal review is $600–$700, up to a possible maximum of around $1,000. For large infrastructure projects, this cost is much less than the usual projected 10% of legal expenses and has the additional benefit of having lawyers accustomed to the contractual terms in case of a dispute arising in the future, as the previously established familiarity with the contract will reduce future dispute times. In addition, these costs are small compared to the costs that may arise from dispute resolution or project delays if there is wrongful drafting or interpretation of contracts.

The participation of lawyers in the procurement process can reduce costs also by ensuring compliance with and the design of dispute boards, which are mandated by World Bank FIDIC contracts but not all FIDIC contracts.

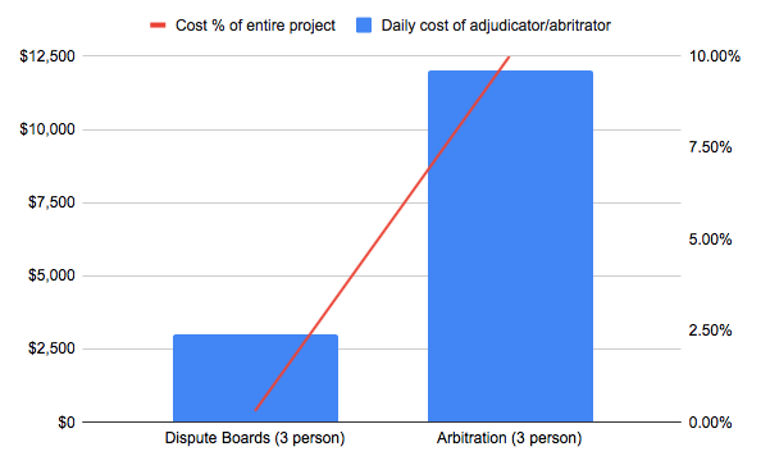

Dispute boards are preferred over litigation and arbitration in terms of the cost and time consumed (see Figure 1). A three-person dispute board tends to cost 0.05%–0.3% of a project’s total costs, while arbitration adds up to about 10% of the project costs (Chapman 2009). In addition, adjudicators’ costs tend to be around $3,000 daily for dispute boards, compared to $500–$1,500 hourly for arbitration. Dispute boards are, therefore, cheaper overall and have the added benefit of alleviating the strain on relationships between parties. This is positive in the context of Asia and the Pacific, where according to Castro (2013), preserving working relations is a top priority. Lawyers can contribute to dispute boards by advising on the suitability of dispute boards for a certain project, drafting dispute board procedures on a case-to-case basis, creating submissions on behalf of clients, and even being members of the boards. The legal background of lawyers also gives more gravitas to decisions made in dispute boards as the conclusion reached will be similar to a conclusion reached in court through litigation, which facilitates the application of non-binding decisions. In addition, because of the lawyer’s previous knowledge of the contract (given participation at the drafting stage), the length of the dispute will be shorter, leading to lower costs.

Source: Chapman (2009); Contracts Counsel (2021); JCAA (2022).

Source: Chapman (2009); Contracts Counsel (2021); JCAA (2022).

To conclude, the initial costs of involving a lawyer in the procurement process, especially for contract drafting and dispute board design, can lead to reduced costs overall given the saved costs on arbitration and project delay and the maintenance of good working relationships. Legal aid can also ensure compliance with FIDIC golden principles while accommodating regional cultural factors, leading to clearer and more just contracts.

1FIDIC refers to Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils, the French name of the federation.

2An analysis and list of the golden principles can be found here.

References

Castro, P. 2013. Case Studies of Using FIDIC in Southeast Asia: “Cultural Sensitivities”. Asia-Pacific FIDIC Contract Users Conference.

Chapman, P. H. J. 2009. Dispute Board on Major Infrastructure Projects. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Management, Procurement and Law 162: 7–16.

Contracts Counsel. 2021. What Does a Contract Review Cost? 19 July. Contracts Counsel.

Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (JCAA). 2022. Arbitration Costs. JCAA.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). 2019. Dispute Board Manual. JICA.

New Engineering Contracts (NEC). 2014. A Comparison of NEC and FIDIC. NEC.

Ong, B., and P. Gerber. 2010. Dispute Boards: Is There a Role for Lawyers? Construction Law International 5(4): 7–12.

Sørensen, J. B. 2022. FIDIC Green Book: A Companion to the 2021 Short Form of Contract. ICE Publishing.

Zheng, X., Y. Liu, R. Sun, J. Tian, and Q. Yu. 2021. Understanding the Decisive Causes of PPP Project Disputes in China. Buildings 11(646).

Comments are closed.