Youth are the future of Southeast Asia. In the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), they constitute 34% of the total population. However, youth have faced unprecedented employment vulnerability due to the global pandemic, threatened by the “triple shock” of job losses, disruption in education and training, and major obstacles to entering the labor market or moving between jobs.

Young people must adapt to a fast-changing regional economy. With the pandemic increasing dependency on digital tools in our daily lives, the economy is also becoming increasingly more digital. Most Southeast Asian countries, except for the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Myanmar, have an internet penetration rate of more than 70% (Statista 2021). During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic alone, internet usage surged by between 50% and 70% globally (Beech 2020). As a consequence of such phenomena, the number of new jobs that require proficiency in digital and improved skills has risen amid a lack of supply of youth workforce able to fulfil such demand.

ASEAN’s digital economy

The share of the digital economy is still only 7% of ASEAN’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Hoppe, May, and Lin 2018), compared to 16% in the People’s Republic of China, 27% in European Union-5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), and 35% in the United States (Thanh and Bich 2019). However, a report by AT Kearney (Chua and Dobberstein 2019) predicts that ASEAN has the potential to enter the top five digital economies in the world by 2025.

A Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company (2021) report on Southeast Asia’s “e-conomy” also highlighted that Southeast Asia is on its way to becoming a $1 trillion digital economy by 2030, with five leading sectors—e-commerce, financial services, online travel, online media, and transport and food—and two nascent sectors that have accelerated rapidly—healthtech and edtech.

Along with the growth of these sectors, new jobs have been generated for 100,000 skilled professionals and 4 million “partners” or workers on flexible schedules who provide daily services such as food delivery, e-commerce logistics, and transportation to customers (Google 2018). As companies like Expedia, Go-Jek, Grab, Meta, Netflix, Lazada, and Sea Group continue their core businesses, it is predicted that they will grow their teams by 10% per year—faster than the general employment growth of 1%–3% in most Southeast Asian countries. Meanwhile, job generation for flexible workers is forecast to increase threefold by 2025.

Can ASEAN youth enter the digital economy?

The answer to whether ASEAN youth can enter the digital economy is, rather, that they will have to. However, despite more jobs being created in the digital economy, ASEAN youth face increased challenges regarding their “readiness”, coupled with the massive drop in employment due to the pandemic. The International Labour Organization (ILO) notes that the employment situation facing young people around the world had still not fully recovered from the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis when the pandemic started (Barford, Coutts, and Sahai 2021).

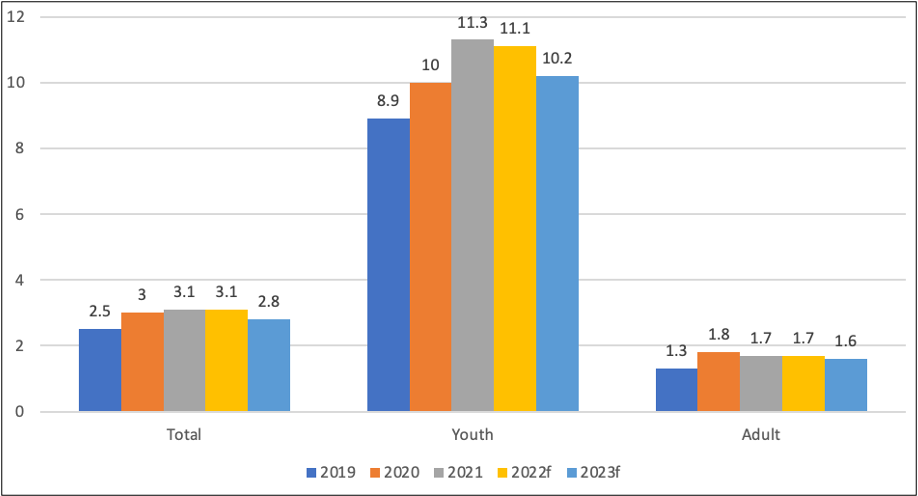

Before the pandemic, the unemployment rate for young people in the region was already high, at 8.9% in 2019 compared to 1.3% among the adult population (Figure 1). The figure rose by 2.4 percentage points, reaching a peak in 2021 at 11.3% of total unemployment among the younger population. This suggests that around 25.4 million youth in ASEAN were left unemployed amid the rise of the Delta variant infections and intensified travel restrictions.

Figure 1. Unemployment Rate in ASEAN Before and After COVID-19 (%)

Note: Data for 2022 and 2023 are forecasted values.

Note: Data for 2022 and 2023 are forecasted values.

Source: ILOSTAT.

The COVID-19 outbreak caused major economic disruptions among employers and workers in the region. The regional economy contracted at a rate of –3.3 % in 2020, freefalling from 4.4% in 2019. The economic contraction not only led to job losses among young people but also disruptions in the school-to-work transition process for more than 15 million new university and school graduates from the 10 ASEAN member countries. The ILO (2021a) reports that in 2020, working hours in ASEAN dropped dramatically by 8.4%, equal to 24 million full-time workers, assuming a 48-hour work week.

The situation has been aggravated by the mismatch between the skills possessed by the current youth labor force and their inability to forecast the potential skillsets that are in demand. A report by LinkedIn (2021), Jobs on the Rise in Southeast Asia, highlights that at least 41 out of 67 rising job positions from 15 job sectors require proficiency in basic digital skills, such as the ability to perform digital marketing skills, operate basic office software (e.g., Microsoft Office), manage cloud computing, and set up internet and digital communications tools. Furthermore, 12 positions require advanced digital skills, such as proficiency in programming, coding, data science and analysis, and UI/UX.

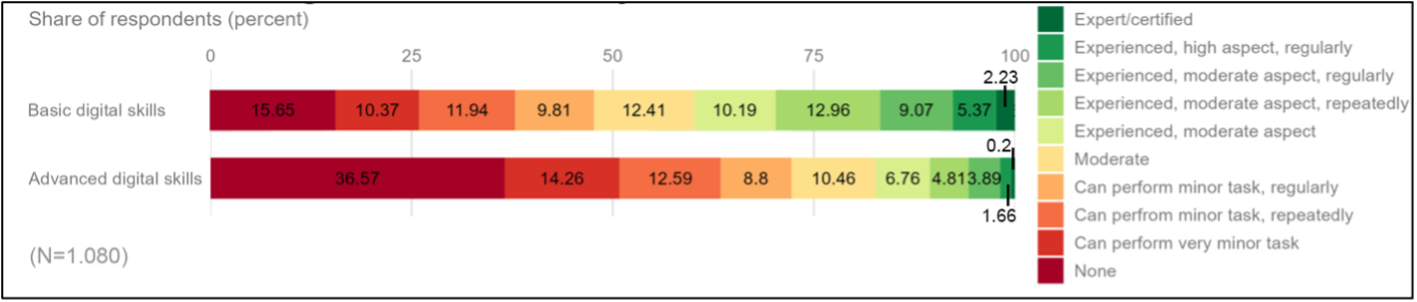

However, a recent study by the ASEAN Foundation and Google.org, Jobs Market and Skills Demand for the Future, reveals a surprising fact regarding the underserved youth (meaning young people who are marginalized as a result of systematic and prolonged inequities and inequalities, such as by economic conditions, being a minority, or holding disability status). The research highlights that of the 1,080 surveyed underserved youth in the region, 47.8% suffer from a lack of skills in functioning basic work software (Figure 2). It also revealed that 72.2% have no or low levels of advanced digital skills.

Figure 2. ASEAN Youth’s Digital Skills Proficiency

Source: Research conducted by LOKA Group.

Source: Research conducted by LOKA Group.

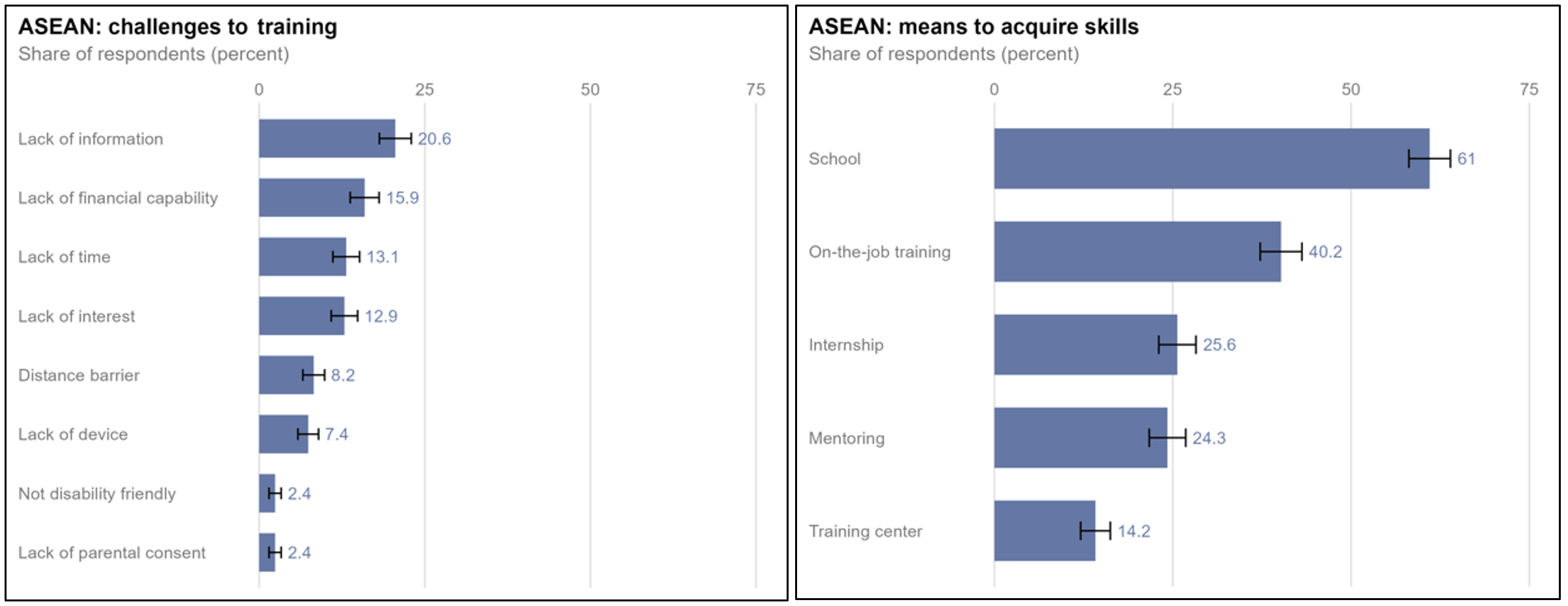

The obstacles to engaging in skilling opportunities vary. School and formal education institutions are top as the means of acquiring skills by 61% in ASEAN (Figure 3). Participation in training centers does not seem to be a popular option for skilling, with only 14.2% of youth participating in them. The three top challenges youth face in terms of training participation are a lack of information (20.6%), lack of financial capacity (15.9%), and lack of time (13.1%).

Figure 3. ASEAN Youth’s Learning Behavior

Source: Research conducted by LOKA Group.

Source: Research conducted by LOKA Group.

Among these top obstacles, Myanmar had the highest percentage of young people reporting a lack of information on the training opportunities available for them. In terms of training non-affordability, the Philippines ranked highest among ASEAN countries, with over 1 in 3 youth responding that their lack of training was due to training opportunities being expensive. Meanwhile, Brunei Darussalam had the highest share of youth experiencing a lack of time to participate in skill development training.

Paving the way for reskilling and upskilling

In November 2022, ASEAN leaders adopted the ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework and its implementation plan during the 37th ASEAN Summit to help minimize the impacts of the pandemic on young people and achieve a sustainable recovery (ASEAN 2020). The Broad Strategy 2 on Strengthening Human Security outlines the priority to promote a contextualized understanding of the 21st century skills that are meaningful for adolescents and youth and aligned with the interests of national economies.

With nearly 70% of youth accessing training from private providers with higher fees than government-funded training, ASEAN governments need to explore possibilities to penetrate the market to safeguard and guarantee inclusive access for youth that have been disproportionately affected during the pandemic. This will help to increase the youth labor force ready to be deployed in the digital economy-based job market once the regional economy bounces back to its peak.

In the wider Asia and Pacific region, more than 86% of youth employment is in the informal sector—more than the proportion of adult workers (ILO 2021b). There is no doubt that the informal economy also accounts for a substantial share of youth employment in ASEAN. Hence, along with the priority to accelerate digital skills penetration among the underserved youth in the region, ASEAN governments should also strengthen social protection schemes by targeting young people as beneficiaries and ensuring that they can learn new skills while balancing and fulfilling their other daily needs.

References

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). 2020. ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework and its Implementation Plan.

ASEAN Foundation. 2022. Mind the Gap: Mapping Youth Skills for the Future in ASEAN.

Barford, A., A. Coutts, and G. Sahai. 2021. Youth Employment in Times of COVID. International Labour Organization.

Beech, M. 2020. COVID-19 Pushes Up Internet Use 70% And Streaming More Than 12%, First Figures Reveal. Forbes.

Chua, S. G., and N. Dobberstein. 2019. The ASEAN Digital Revolution. Kearney.

Google. 2018. E-Conomy Southeast Asia 2018: Southeast Asia’s Internet Economy Hits an Inflection Point. Google and Temasek.

Google. 2021. E-Conomy Southeast Asia 2021: Roaring 20s: The SEA Digital Decade. Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company.

Hoppe, F., T. May, and J. Lin. 2018. Advancing Towards ASEAN Digital Integration. Bain & Company.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2021a. COVID-19 and the ASEAN Labour Market: Impact and Policy Response. ILO.

ILO. 2021b. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Asia and the Pacific. ILO.

LinkedIn. 2021. Jobs on the Rise in Southeast Asia 2021. LinkedIn.

Statista. 2021. Internet penetration in Southeast Asia as of June 2021. Statista.

Thanh, V. T., and D. I. N. Bich. 2019. Building an Inclusive Digital ASEAN by 2040. The Jakarta Post, 7 September.

Comments are closed.