Local currency bond markets (LCBMs) have continued to develop in emerging Asian economies since the early 2000s, with foreign investor participation rising markedly since the global financial crisis of 2007–2008. LCBMs help to enhance domestic financial stability by enabling governments and companies to borrow in domestic currency. The resulting reduction in the reliance on foreign currency borrowing mitigates exposure to external financial shocks. More specifically, the issuance of bonds denominated in domestic currency helps economies alleviate their exposure to exchange rate risk in the bond market (so-called “currency mismatch”).

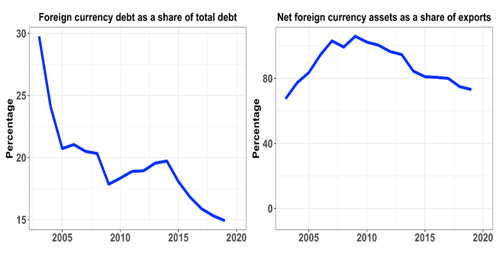

In addition, LCBMs enable a lengthening of the maturity of the stock of debt. Previously, the short-term borrowing of foreign currency in conjunction with the long-term lending of domestic currency led to “maturity mismatches” in the bond market. With LCBMs, the extent of these currency and maturity mismatches, which were amplifiers of financial distress during the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998, is alleviated, and economies are less reliant on foreign and short-term debt.1 The share of foreign currency debt in emerging Asia, while still pervasive, has continued on a downward trajectory as a result (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Foreign Currency Debt and Currency Mismatches in Emerging Asia

Note: Emerging Asia comprises the People’s Republic of China (PRC); Hong Kong, China; India; Indonesia; the Republic of Korea; Malaysia; the Philippines; Singapore; Thailand; and Viet Nam. The data is computed as GDP-weighted averages for the 10 economies in the sample.

Source: Authors’ calculations with data from the International Monetary Fund, Bank for International Settlements, Institute for International Finance, and China Economic Database.

Foreign investors have been attracted to LCBMs in search of returns, notably in the aftermath of the very low global interest rate environment of the global financial crisis (Miyajima, Mohanty, and Chan 2015). This has helped LCBMs to develop further. However, the increasing presence of foreign investors in these markets may amplify the risk of capital flow reversal in periods of heightened financial tension. This is due to the currency risk borne by foreign investors in LCBMs, a risk they are largely unable to hedge against due to the lack of sufficiently developed derivatives markets.

Therefore, while LCBMs help to address currency mismatch for domestic investors, foreign participation in LCBMs equates to a shift in the currency mismatch to foreign investors (Carstens and Shin 2019). Moreover, some empirical evidence suggests that while foreign investor participation in LCBMs can help to increase market liquidity and lower bond yields, the volatility of yields tends to increase (e.g., Ebeke and Lu [2015]). In addition, LCBMs tend to be more susceptible to global financial shocks when foreign participation in LCBMs exceeds a given threshold, while the diversification benefits can be negatively affected in the presence of high exchange rate volatility (Turner 2012). Foreign investors in LCBMs also tend to be more responsive to changes in global interest rates than domestic investors, which can amplify the exposure of LCBMs to foreign shocks.

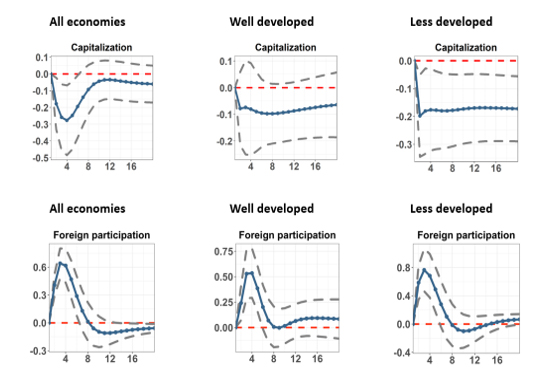

Building on the prevailing literature, a new paper by Beirne, Renzhi, and Volz (2021) examines the role of foreign investor participation in LCBMs over the period 1999–2020 for a sample of 10 emerging Asian economies. Using panel regression techniques and impulse responses generated from a structural vector autoregression, the authors find that economies with less developed LCBMs are more susceptible to capital flow volatility due to foreign investor participation than those with more developed LCBMs. Figure 2 shows the reaction of capital flow volatility in emerging Asian LCBMs to shocks imposed on LCBM capitalization and foreign investor participation in LCBMs.

Figure 2: Responses in Capital Flow Volatility to Shocks Imposed on LCBM Capitalization and Foreign Investor Participation in LCBMs

Notes: “Well developed” and “less developed” refer to economies with an average LCBM capitalization/GDP ratio that is higher and lower, respectively, than the regional average over the period 1999–2020. Median responses with 95% confidence bands are shown as dashed lines. The unit of the shock is 1 percentage point, and the units of the horizontal axes refer to the number of months.

Source: Beirne et al. (2021).

Whereas positive LCBM capitalization shocks help to stabilize capital flows, in line with expectations as LCBMs grow and become more liquid, the opposite effect is found for foreign investor participation shocks, albeit with less persistence. Moreover, the sharp increase in capital flow volatility from these latter shocks is much more pronounced for less developed LCBMs. More specifically, a positive shock to foreign investor participation (i.e., a rising foreign investor share in LCBMs) of 1 percentage point yields a rise in capital flow volatility in less developed markets by around 0.8 percentage points at peak. This compares to around 0.5 percentage points for well-developed markets. The impact on capital flow volatility dissipates and becomes insignificant after around 6 months. Therefore, while foreign participation in LCBMs helps the development of these markets and provides important risk-sharing and diversification benefits for LCBMs, policy makers should be cautious of the potential financial stability risks.

A policy implication for emerging Asian economies is to seek to develop further their LCBMs and, in particular, to strengthen the domestic investor base, which tends to be less sensitive to fluctuations in global foreign exchange and interest rate developments, and have longer-term investment horizons. Moreover, the development and enhancement of currency hedging capabilities in emerging Asia may help foreign investors to deal more smoothly with currency fluctuations and help to dampen capital flow volatility.

_____

1 Other benefits of LCBMs include the ability to better manage capital flow volatility, reduced global imbalances, alleviation of the need to hold large foreign reserves, and the facilitation of smoother balance sheet adjustment (thereby enabling macroeconomic policy to adjust to shocks more smoothly). See International Monetary Fund (2016) for further details.

References:

Beirne, J., Renzhi, N., and Volz, U. 2021. Local Currency Bond Markets, Foreign Investor Participation and Capital Flow Volatility in Emerging Asia. Singapore Economic Review. (published online on 17 June 2021).

Carstens, A., and H.-S. Shin. 2019. Emerging Markets Aren’t Out of the Woods Yet. Foreign Affairs, 15 March.

Ebeke, C., and Y. Lu. 2015. Emerging Market Local Currency Bond Yields and Foreign Holdings: A Fortune or Misfortune? Journal of International Money and Finance 59(C): 203–219.

International Monetary Fund. 2016. Development of Local Currency Bond Markets: Overview of Recent Developments and Key Themes. Staff Note for the G20 IFAWG, Seoul, 20 June.

Miyajima, K., M. S. Mohanty, and T. Chan. 2015. Emerging Market Local Currency Bonds: Diversification and Stability. Emerging Markets Review 22: 126–139.

Turner, P. 2012. The Global Long Term Interest Rate, Financial Risks, and Policy Choices in EMEs. BIS Working Paper No. 441. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

Comments are closed.