Income growth, urbanization, nutritional awareness, and supermarket revolutions in Asia are fueling demand for high-value agricultural products (HVPs), such as vegetables and fruits. This change in consumer demand can provide new agri-food market opportunities, which in turn can contribute to numerous Sustainable Development Goals through increased rural income, rural livelihood improvement, and rural poverty reduction. However, the transformation of Asian agriculture toward the production of HVPs has been slow compared with the changes in market demand. Why is it difficult, especially for smallholder farmers and small agro-processors, to turn the high-quality standards demanded by markets into market opportunities? This is because of a lack of information and knowledge and a lack of access to credit, quality inputs, and machinery (Otsuka and Zhang 2021).

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has accentuated the need for HVP value chain development to generate new income and employment opportunities in rural areas. Moreover, the transition toward HVP-oriented agriculture is essential for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of no poverty, zero hunger, and good health and well-being. Enhancing farm income is also vital for achieving food security and promoting sustainable agriculture. Therefore, the central question is how to promote the transition toward HVP-oriented agriculture in Asian countries.

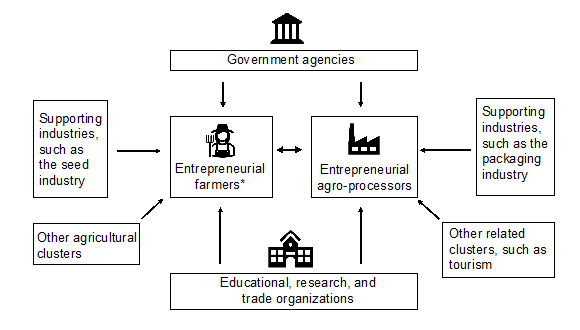

One of the most promising strategies is the cluster-based development approach. Clusters are defined as “groups of industries closely related by skill, technology, supply, demand and/or other linkages” (Delgado, Porter, and Stern 2016). A cluster-based development approach involves collaborative actions by groups of companies, governments, and other related institutions to improve the competitiveness of a group of interlinked economic activities in a specific geographic region (Ketels and Memedovic 2008). Sonobe and Otsuka’s (2006) empirical study of cluster-based industrial development in developing countries suggests that a cluster can be an effective institution for HVP value chain development as well. Indeed, Gálvez-Nogales (2010) finds numerous successful agro-based clusters in many countries. As an illustration, Figure 1 shows the structure of an agro-based cluster. In the cluster, farmers are entrepreneurs who see their farms as businesses. They are not just farming but operating complicated businesses, employing workers, coordinating the division of labor among teams, and collaborating with outsiders. In other words, entrepreneurial farmers are skillful at not only producing but also grading, marketing, branding, and management. Under the cluster, entrepreneurial farmers and entrepreneurial agro-processors are closely connected through contracts, and they also enjoy linkages with (i) local institutions, such as government agencies; (ii) industries supporting crop cultivation, such as the seed industry; iii) industries supporting crop processing, such as the packaging industry; and iv) other related industries, such as tourism (Otsuka and Ali 2020; Porter 1998).

Figure 1: Structure of an Agro-Based Cluster

* Entrepreneurial farmers are skillful at not only producing but also grading, marketing, branding, and management.

Source: Authors.

The cluster approach can enable smallholder farmers and agro-processors to engage in high-value agriculture through at least two key mechanisms. The first mechanism is knowledge and information spillovers. The vertical and horizontal coordination between actors in the agricultural value chain and supporting organizations will foster trust, reduce transaction costs, and facilitate the flow of knowledge and information. Knowledge and information transfers will then promote the diffusion of technological and managerial innovations. These innovations are important because, in high-value agriculture, good performance by a cluster member can boost the success of the others. For example, the performance of agro-processors is highly dependent on the crop quality produced by farmers. The second mechanism is collective actions. Organizations within a cluster can be used as a means to consolidate marketing operations, such as market research and crop quality certifications. These collective actions will substantially reduce the transaction costs of individual farmers and agro-processors, thereby allowing each member to enjoy low transaction costs as if it had greater scale. Moreover, farmer organizations will also enable smallholder farmers to access credit, quality inputs, and machinery (Bizikova et al. 2020).

Otsuka and Ali (2020) propose five strategies for the development of agro-based clusters in developing countries. First, stakeholders within a cluster must be mobilized into various groups, such as farmer cooperatives and agro-processors’ associations. Second, stakeholders in the cluster must be trained through their groups. Specifically, training for improved cultivation practices must be offered to farmers, seed companies, and nursery operators. Moreover, farmers should be trained in grading, marketing, and management. Besides, managerial training must be offered to agro-processors. Third, the collective actions within each group and the vertical linkages between farmers and agro-processors through contracts must be promoted. Fourth, a regulatory framework to implement quality standards must be set up. Finally, a project management unit must be established to coordinate the interests of diverse stakeholders and promote the cluster-based agricultural transformation approach.

Research and development are required to support the transition toward high-value agriculture through the cluster-based development approach. Although there is a wealth of research and initiatives relating to cluster development in various industries, little attention has been paid to clusters in the agricultural sectors (Gálvez-Nogales, 2010). Therefore, the international research community can contribute to the transition by helping to design an effective strategy to develop agro-based clusters in developing countries. Moreover, governments and donors can contribute by providing support to research programs that aim to deepen our understanding of agro-based cluster initiatives, structure, and outcomes.

_____

References:

Bizikova, L., E. Nkonya, M. Minah, M. Hanisch, R. M. R. Turaga, C. I. Speranza, M. Karthikeyan, L. Tang, K. Ghezzi-Kopel, J. Kelly, A.C. Celestin, and B. Timmers. 2020. A Scoping Review of the Contributions of Farmers’ Organizations to Smallholder Agriculture. Nature Food, 1: 620–630.

Delgado, M., M. E. Porter, and S. Stern. 2016. Defining Clusters of Related Industries. Journal of Economic Geography, 16: 1–38.

Gálvez-Nogales, E. 2010. Agro-Based Clusters in Developing Countries: Staying Competitive in a Globalized Economy. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Ketels, C. H. M., and O. Memedovic. 2008. From Clusters to Cluster-Based Economic Development. International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development, 1: 375–392.

Otsuka, K., and M. Ali. 2020. Strategy for the Development of Agro-Based Clusters. World Development Perspects, 20: 100257.

Otsuka, K., and X. Zhang. 2021. Transformation of the Rural Economy. In Agricultural Development: New Perspectives in a Changing World, edited by International Food Policy Research Institute: 359–369.

Porter, M. E. 1998. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harvard Business Review.

Sonobe, T. and K. Otsuka. 2006. Cluster-Based Industrial Development: An East Asian Model. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Comments are closed.