ESG investment aims to encourage companies to consider environment (E), social (S), and corporate governance (G) issues by raising their long-term corporate value. It is becoming indispensable for filling the funding shortfalls needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the global temperature increase this century to well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, and desirably within 1.5 degrees Celsius, as well as to encourage the transformation of corporate behavior toward net-zero emissions.

Growing but still inadequate funding

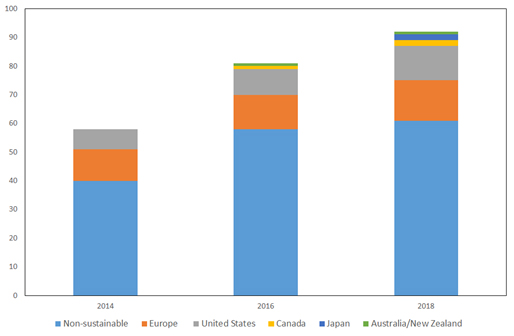

Several data indicate a steady, but still limited, increase in long-term-oriented ESG funds. According to data compiled by the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), the amount of sustainable investing assets managed by major asset managers and owners globally rose from $23 trillion in 2016 to $31 trillion in 2018 (Figure 1). This accounted for one-third of global total investment assets, including non-sustainable or regular types of investment. Europe and the United States (US) dominate, comprising 45% and 38% of the total, respectively. The GSIA’s sustainable data cover more than green assets and include stocks, bonds, private equity, loans, real estate, and other assets.

Figure 1: Sustainable Investment by Major Economies and Non-Sustainable Investment ($ trillion)

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance and the Ministry of Environment of Japan.

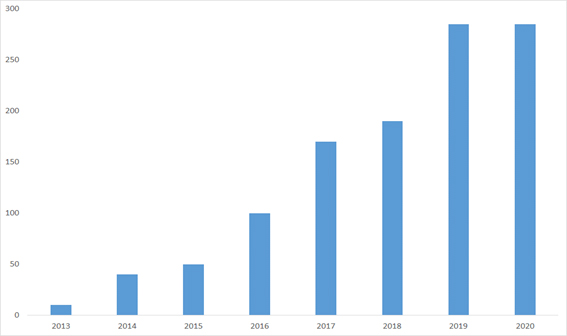

Second, green bond data compiled by Moody’s Investors Service and the Climate Bonds Initiative show that the amount of newly-issued green bonds rose from $100 billion in 2016 to around $296 billion in 2020 globally (Figure 2). Most of these bonds were issued by governments, agencies, and companies in Europe, followed by those in the US, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and Japan.

Figure 2: Issuances of Green Bonds ($ billion)

Sources: Moody’s Investors Service and Climate Bonds Initiative.

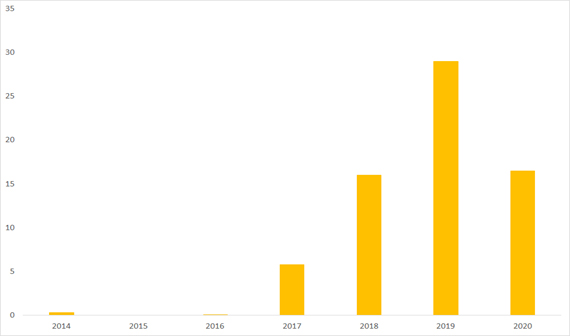

Third, data on green loans complied by Environmental Finance and the Ministry of Environment of Japan indicate that the size of green loans is small, but surged from $1 billion in 2016 to $29 billion in 2019. The amount dropped to $16.5 billion in 2020, however, due to the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic (Figure 3). Most of these green loans originated in Europe.

Figure 3: Amount of Green Loans ($ billion)

Source: Environmental Finance and Ministry of Environment of Japan.

While all these green funds are on a rising trend, their amounts are insufficient to achieve net-zero carbon emissions. More funds should be allocated to innovative firms and essential projects in the areas of renewable energy, electronic vehicles, storage batteries, hydrogen technology, and carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS), etc. The 2018 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5℃ published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimated that the necessary annual financing amount could be around $2.4 trillion on average from 2016 to 2050, or a total amount of about $82 trillion. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, UN Environment, and the World Bank (2018) estimated that around $6.3 trillion is needed each year for infrastructure investment just to meet the 2030 emission goal consistent with the Paris Agreement’s goal.

Overcoming greenwashing problems with better information infrastructure

ESG investment is also an essential tool for influencing corporate behavior, as firms often find it difficult to rapidly transform their businesses voluntarily, despite the awareness of the need to decarbonize their business models. ESG investors can be more patient than general investors and communicate with targeted firms repeatedly to advise them to take the necessary steps. Meanwhile, ESG investors have been concerned about “greenwashing” problems—namely, the behavior of companies that attempt to exaggerate or provide misleading or false information for the purpose of providing the impression that their products or services are environmentally sound (Kalesnik, Wilkens, and Zink 2020). To mitigate these problems, green bonds and loans must ensure rigorous, independent, and quantitative assessments of outcomes. Sustainability-link bonds could be more useful, as they set performance targets (such as for greenhouse gas emissions) and adjust the coupon interest rates according to the actual performance relative to the targets. The situation must be avoided where borrowing firms continue to increase emission-intensive activities using regular bonds or loans. On this front, ESG shareholders play an important role because of their ability to communicate with firms through engagement and, if necessary, to exercise voting rights against their management teams in the event of inactions.

To mitigate greenwashing and, thus, attract more investment, the world should collectively work on defining green taxonomy (environmentally sustainable or green activities) as well as transition activities that are not green but are needed in the transition process toward net-zero emissions. A working group co-chaired by the European Union and the PRC to bring together common views on taxonomy is a welcome step for promoting the standardization of such activities. Without some degree of consensus, setting a carbon border adjustment mechanism aimed at avoiding carbon leakages unilaterally by some economies may generate international frictions. Such a tool could also be used as an excuse to protect domestic industries. As carbon-free technology can be associated with national or regional security matters, this perspective cannot be taken lightly.

To increase ESG investment, the world must also overcome the difficulties in assessing firms’ environmental sustainability from publicly disclosed information owing to the diversity of indicators and definitions adopted by firms. The proliferation of nonfinancial guidelines by standard setters—while helping to promote disclosure and transparency—has been burdening firms in preparing for the various requirements. Large variations in the ESG scores assigned by ESG assessment companies for the same firms can confuse passive investors. Moreover, a high score for climate change does not necessarily indicate that a firm’s emission targets and strategies are in line with the Paris Agreement’s goal. Therefore, the integration of various standards and guidelines led by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation would be a welcome step to promoting the standardization of the disclosure of nonfinancial information among listed companies.

It is widely accepted that climate-related information disclosure should be made according to the recommendations published by the private sector Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Information Disclosure (TCFD). The United Kingdom took the lead by making it mandatory for listed firms to disclose information based on TCFD recommendations starting from 2021. It is desirable for governments to introduce mandatory requirements for including the 2030 and 2050 emission targets and Scope 3 coverage along the supply chain network. Participating in the Science Based Targets initiative and RE100 are other ways to promote environmental sustainability. As greater ESG investment requires urgent improvements in the information infrastructure, strong leadership and aspirations from all countries and firms will be indispensable.

_____

References:

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2018. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5.

Kalesnik, V., M. Wilkens, and J. Zink. 2020. “Green Data or Greenwashing? Do Corporate Carbon Emissions Data Enable Investors to Mitigate Climate Change?”, mimeo.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, UN Environment, and the World Bank. 2018. Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure, Policy Highlights.

Comments are closed.