Over the next 3 decades, about 70% of the world’s population is expected to be living in urban areas. Within the next decade, by 2030, the world is projected to have over 40 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants. Such population flows into cities will disrupt the functioning of cities and lead to urban issues, such as transportation congestion, air pollution, and housing shortages.

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has presented an unprecedented case in the history of global economics. The pandemic has left many countries with no choice but to enforce lockdowns.1 Crucially, a country’s economy depends on consumer spending behavior, while at the same time, consumer behavior is also linked to quality of life. The unprecedented change in the discourse of the global economy and local development suggests severe implications for livability and quality of life at the city level.

In addition, growth in urbanization has not only economic implications but also environmental impacts. In recent times, issues related to climate change, such as heat waves, heavy precipitation, and droughts, have occurred in cities more frequently, adding to the existing complexities of urban disaster risk management (United Nations 2014; UN Habitat 2016). Urban planners have been making efforts to find solutions for these challenges that are detrimental to the livability of cities.

Since the beginning of civilization, humankind has been fascinated by the built environment. Utopian attempts like Arcoscanti, Auroville, and others have pushed the boundaries of merging the built environment with sustainable living, attracting thousands of people in search of a quality living experience. However, quantifying quality of life is difficult, and there exist several different types of indexes that define or label cities as sustainable, livable, global, smart, or resilient, among others. Regardless of how these concepts are understood in the planning of cities, their categorization is often a subset of the historical past through which the cities have survived. Moreover, there are different scales for ranking cities that accompany these concepts that enable users to appropriate which cities are more sustainable, livable, or global.

The results of such rankings are broadcast in different media, allowing people from around the world to choose which cities they would like to live in. However, the major question arises: Based on the results, can we decide which cities are the best to live in? Rankings may show different results depending on their evaluation criteria. Meanwhile, a ranking that covers a large number of cities may have advantages for comparison purposes, but greater coverage requires a ranking to implement diverse evaluation criteria, which may reduce the relevance of the results if there is not sufficient data availability.

With such complexity, how should we decide which city is the best? City planners and government officials, in particular, are eager to know which city is the best or how the cities where they currently live or work are ranked? Such results can be crucial to help promote cities or to establish them as benchmark reference points for future planning.

On the other hand, since we are living in an era of globalization, people around the world are becoming increasingly able to move quickly and easily to more comfortable and business-friendly cities. Cities no longer mainly rely on suburbs to provide their workforce but compete globally to attract better human resources, especially the “creative class”, for their continuous growth (Florida 2012). If a city is successful in attracting an appropriate creative class, it can move toward becoming an efficient knowledge hub that provides unique opportunities for its citizens and a conducive environment for successful businesses. Furthermore, the variety of businesses may diversify with the influx of qualified human resources, awareness of higher education may be raised, and a city can be torqued in a virtuous cycle of growth for its businesses and citizens.

A further difficult challenge is to understand, what would make a city best for all kinds of people? Citizens are each at different stages of life, with different backgrounds, preferences, and skills. It can indeed be useful to know the ranking of results in order to grasp updates on cities, but even the best city cannot fit the needs and wants of all, let alone inform the public about what is good for their personal growth.

Thus, it is more important to know the features of cities in order to evaluate whether those cities are suitable for certain individuals and lifestyles. Moreover, rankings of cities vary with the adopted ranking systems, as most of the rankings are produced by people who do not actually live in those cities on the list. If the features of the cities can be explained by actual residents who are specialized in the field of urban planning, the presented features may be more reliable and accurate.

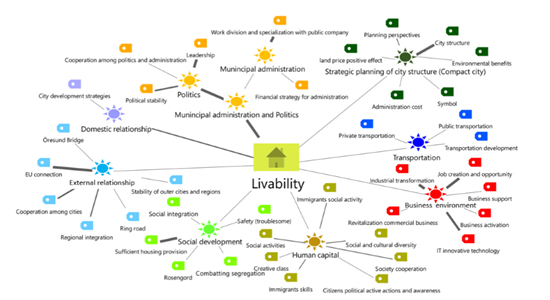

Takahashi et al. (2018)2 demonstrate a method of grasping a city’s features through a field survey of Malmö, Sweden. The study presents the transition process that businesses in Malmö underwent to attract a “creative class”, which helped to transform the city from being heavily industrial to becoming a knowledge-based city. The study further notes the overall transition within the city of Malmö. The method shows a visualization of the city’s features, providing an overview that can be understood easily and quickly. Furthermore, the visualization encapsulates both the strengths and challenges of the city. According to the obtained results, the actual challenges for livability for Malmö were (1) the shortage of housing infrastructure due to the population influx from outside of Malmö and (2) security concerns caused by social inequality in certain areas that accommodate immigrants.

Figure 1: Visualization Map of Case Study of Malmö

Source: Takahashi et al. (2018).

In order to overcome these challenges, the city government is focusing on the reduction of regional inequality. The Malmö City Government has implemented public transport projects that act to avoid the isolation of areas and maintain land values in urban areas. The existing city rankings tend to suggest only results, but this method can tell a city’s story behind the ranking results. Moreover, it also assists in determining the future trajectory of the city.

The visualization method is still at the conceptual stage, but with rising urban populations, such methods can aid in determining the livability of any given city. A dashboard of city indices in the form of feature visualizations of different cities would allow global citizens to make choices for their own growth and would be helpful to inform city officials and experts on the key issues and challenges related to sustainable development and livability in cities.

_____

1 Why is Coronavirus Causing a Recession? Shreyas Bharule blog, 27 May 2020.

2 This paper was presented by Kyoko Takahashi at the ADBI seminar, Sustainable Urban Development in the context of Livability in Cities, on 26 September 2019.

References:

Florida, R. 2012. The Rise of the Creative Class, Revisited. CityLab, 25 June.

Takahashi, K., S. Kudo, E. Tateishi, N. Furukawa, J. Nordqvist, and D. Ingosan Allasiw. 2018. Identifying Context-Specific Categories for Visualizing Livability of Cities—A Case Study of Malmö. Challenges in Sustainability, 6.1(2018): 52–64.

UN Habitat. 2016. World City Report 2016 (accessed 22 June 2017).

United Nations. 2014. World Urbanization Prospects (accessed 6 May 2017).

Comments are closed.