Currently at the frontier of financial development, cryptocurrency provides both opportunities and risks in financial markets and has driven a large interest in its early years. The new business model provided by cryptocurrency along with the exponential increases in its prices may have enticed investors, with many utilizing cryptocurrency as a speculative asset to take advantage of the early gains. However, the subsequent crash in prices provided a wake-up call to speculators dealing with cryptocurrency. Additionally, risks related to price manipulation in cryptocurrency markets are not unheard of (Gandal et al. 2018).

Although many central banks have issued warnings about the use of cryptocurrency and explicitly denied its status as a currency, only few have banned its use as a financial asset. Policy makers are concerned about the low liquidity, use of leverage, market risks from volatility, and operational risks of cryptocurrency (Financial Stability Board 2018). Many central banks emphasize that cryptocurrency is not legal tender and that users face the risk of unenforceability of cryptocurrency transactions. The Global Legal Research Center (2018) compiled regulations on cryptocurrency and its report shows that cryptocurrency can be legally traded in countries where it is allowed as long as it follows existing rules or laws related to financial instruments. Regardless of the regulatory stance, policy makers are wary that cryptocurrency would be used for illegal activities, such as money laundering, trade in illegal or controlled substances, or terrorism finance. Policy makers are also aware of the potential lack of consumer and investor protection. Deposit insurance for holders of cryptocurrency is limited and not supplied by domestic monetary authorities. The combination of the potential benefits and macroeconomic risks of cryptocurrency begs the question of what determines policy openness or aversion.

Cryptocurrency in emerging Asia

The implications of the development of cryptocurrency resonate with the lessons from the Asian financial crisis in 1997, which includes the importance of sequencing financial reforms with the de jure capital account liberalization. In addition, the crisis emphasized the importance of early warning systems to detect risks and vulnerabilities stemming from large and volatile capital flows brought about by speculation. The prudence exercised by Asian economies after the Asian financial crisis insulated these countries from exposure to toxic subprime loans and related financial instruments that triggered the 2008 global financial crisis. In addition, the financial reforms implemented by these economies built up their resilience which allowed them to escape virtually unscathed at the beginning of the crisis.

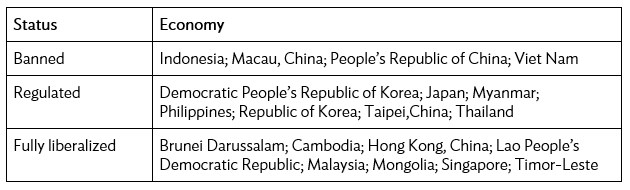

We can observe similar prudence adopted by some Asian economies in treating cryptocurrency (see table). For instance, the Global Legal Research Center (2018) reports that Indonesia forbids the use of virtual currencies as payment in accordance with Bank Indonesia Regulation No. 18/40/PBI/2016 on Implementation of Payment Transaction Processing and Regulation No. 19/12/PBI/2017 on Implementation of Financial Technology. Moreover, Viet Nam similarly prohibits the use of cryptocurrency for payment and other transactions. Prudence may also take the form of imposing regulations or surveillance systems to monitor the market actors involved in cryptocurrency as well as to detect potential suspicious activities. The Government of Thailand also has enacted regulations to govern cryptocurrency. Meanwhile, the Philippines requires businesses engaging in cryptocurrency to register with Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. The Republic of Korea and Japan, two of the biggest markets of cryptocurrency to date, are actively watching market developments and revising their regulations and supervision accordingly. While currently not explicitly regulating cryptocurrency, Malaysia is in the process of finalizing its regulations.

Cryptocurrency Regulation in East and Southeast Asian Economies

Source: Authors’ categorization of the regulatory stance.

Policy implications

In a new ADBI working paper (Shirakawa and Korwatanasakul 2019), we assess how effective governance institutions and de jure financial openness influence the attitude of policy makers in pursuing further financial development by allowing the use of cryptocurrency. Our results reaffirm previous findings that institutional quality contributes to financial development. Putting it differently, the results imply that a certain level of institutional quality may be necessary before opening up to new forms of financial technology.

Furthermore, policy makers may consider the different pace in development of institutions and the financial market. Financial market developments appear to outrun institutional development. In 2011, other cryptocurrencies emerged; this was 3 years after the inception of Bitcoin in 2008 (Farell 2015). In this short period of time, various players joined to take advantage of the opportunities. Since then, several legal and security problems have also emerged. In the meantime, the pace of strengthening institutions by enhancing bureaucratic effectiveness or the credibility of legal systems may not keep up with the demands of the finance sector. Some policy makers and industry players acknowledge the gap in institutional capacity to regulate and intervene, thus advocating a hands-off government approach to market development. Nevertheless, whether governments decide to intervene, regulate, or let markets be, the quality of governance gives policy makers the credibility in enforcing their policy choice. Trust in the system can facilitate financial development. Hence, improving institutions could still be a worthwhile aim moving forward, even if it is outpaced by financial development.

Finally, the decentralized and international nature of the cryptocurrency industry underlies a need for international cooperation. Standing issues include avoiding potential circumvention of regulation and supervision in the international trade of cryptocurrency, particularly for preventing money laundering or terrorism finance. Policy makers also need to be vigilant of potential spillover effects of volatility in the cryptocurrency market. Increasing macrofinancial linkages could make the real sector vulnerable to amplified adverse effects coming from new financial technology, especially if the presence of cryptocurrency continues to rise in coming years.

_____

References:

Farell, R. 2015. An Analysis of the Cryptocurrency Industry. Wharton Research Scholars, 130.

Financial Stability Board. 2018. Crypto-asset Markets: Potential Channels for Future Financial Stability Implications.

Gandal, N., J. Hamrick, T. Moore, and T. Oberman. 2018. Price Manipulation in the Bitcoin Ecosystem. Journal of Monetary Economics. 95. pp. 86–96.

Global Legal Research Center. 2018. Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World. Library Law of Congress.

Shirakawa, J.B.R., and U. Korwatanasakul. (2019). Cryptocurrency Regulations: Institutions and Financial Openness. ADBI Working Paper 978. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Comments are closed.