Measuring productivity in the services sector is fraught with difficulties. One key aspect of the “premature deindustrialization” argument is the hypothesis that services are low productivity relative to manufacturing, and that prospects for rapid and sustained productivity growth, which are the primary source of gains in per capita income, are greater in manufacturing than in services.

Measuring productivity in the services sector is fraught with difficulties. One key aspect of the “premature deindustrialization” argument is the hypothesis that services are low productivity relative to manufacturing, and that prospects for rapid and sustained productivity growth, which are the primary source of gains in per capita income, are greater in manufacturing than in services.

Rodrik (2016) argues that manufacturing has a special role in development and growth, as it is technologically dynamic and tradable (i.e., not constrained by small domestic markets). In a recent study (Shepherd 2019), we take a different approach, focused on trade data. Productivity differences are a key driver of trade flows between countries, according to Ricardian logic. If the relative productivity hypothesis behind the premature deindustrialization argument is true, we would expect to see it reflected in trade data. Specifically, we would expect countries to experience different patterns of revealed productivity growth between manufacturing and services.

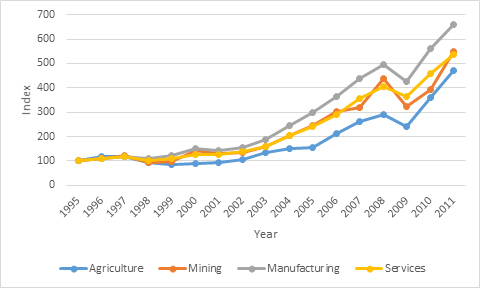

Figure 1 shows growth in nominal gross exports over time, with all sectors re-based to equal 100 at the beginning of the sample (1995), so that changes can be interpreted in percentage terms. Although growth in manufactured goods exports outstripped that of other sectors in the golden age of development of “Factory Asia,” services in fact also enjoyed explosive export growth over time. The significant difference between manufacturing and services by 2011 is due to compounding over time. In fact, average annualized growth rates were very close: 12.5% per annum for manufacturing and 11.1% per annum for services. In any other environment, such a growth rate of services exports would be considered evidence of rapid and successful development of the services sector. Comparing rates of growth across macro-sectors suggests that although developing Asia enjoys a comparative advantage in manufacturing relative to all other sectors, there is nonetheless evidence of a comparative advantage in services relative to agriculture and, arguably, mining. In other words, the secondary and tertiary sectors are both sources of comparative advantage relative to the primary sector. From a development standpoint, this finding is important, as it suggests that movement out of low-productivity agriculture is benefiting both the manufacturing and services sectors. Second, these data do not support the assertions that manufactured goods are tradable in a way that services are not, nor that they have prospects for dynamic growth that services do not.

Figure 1: Exports by Macro-sector, Developing Asia, 1995=100

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database; and author’s calculations.

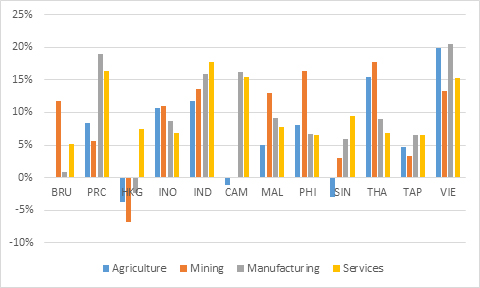

Of course, even the relatively small sample of economies used in this analysis displays significant heterogeneity. To make this clear, Figure 2 shows average annualized growth rates of exports in each macro-sector for our developing Asia sample. In Brunei Darussalam; Hong Kong, China; India; Cambodia; the Philippines; Singapore; and Taipei,China, the growth rate of services exports is either higher than the growth rate of manufacturing exports, or is very close to it. Even in a manufacturing powerhouse such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the two rates are surprisingly close, as they are again in Malaysia, a country that is relying heavily on manufacturing in its effort to move from middle- to high-income status. The overall conclusion from Figure 2 is that there is a broad basis for arguing that services are a vital component of total trade growth in developing Asia.

Figure 2: Average Annualized Growth Rates of Exports by Macro-sector, 1995-2011, Developing Asia

Source: OECD-WTO TiVA database; and author’s calculations.

To formalize these insights, we make use of a recently developed Ricardian model of trade (Costinot, Donaldson, and Komunjer 2012). Under Ricardo’s logic, one important driver for trade is not absolute differences in productivity, but relative differences. In other words, we are interested in whether the PRC or Singapore is relatively better at producing financial services relative to electronics. A by-product of their model is a simple and intuitive methodology for estimating a theory-consistent measure of revealed comparative advantage using a standard gravity model. They take their insight to the data using trade in goods only, and their work has been extended to a more disaggregated level by Lemain and Orefice (2013). To our knowledge, this is the first application of the same methodology to services, in particular to allow for patterns of comparative advantage across goods and services sectors.

Results show that developing Asia typically has a comparative advantage in manufacturing sectors relative to agriculture. The most important point, however, is that the degree of advantage varies considerably across countries within sectors and across sectors within countries. Similarly, there is no simple conclusion to be drawn about relative patterns of comparative advantage in goods and services in developing Asia. Results are highly variable across countries and sectors, but there are many instances in which developing Asian economies have a comparative advantage in services subsectors relative to agriculture and in certain services subsectors relative to some manufacturing subsectors. In the PRC, for example, the extent of the comparative advantage in wholesale and retail trade relative to agriculture is comparable to that for textiles and clothing or machinery in manufacturing. Similarly, the degree of comparative advantage of the Philippines in transport services relative to agriculture is stronger than what is observed in all manufacturing sectors except for electronics.

The key conclusion is that policy makers should be wary of oversimplifying the relationship between manufacturing and services. On the one hand, the servicification of economies all around the world (e.g., Bamber et al. 2017), including in Asia, means that it is now quite impossible to talk about trade or productivity growth in manufacturing without considering services inputs. On the other hand, we have also shown that the experience of developing Asia has not been that countries choose “manufacturing” or “services” in an aggregate sense, potentially at the expense of the other, but that the two interact in complex ways. Similarly, our results suggest that “services pessimism” in developing Asia—the idea that only manufacturing can produce rapid and sustained productivity growth—is not warranted as a general proposition. Rather, we see that in individual countries, particular services subsectors have exhibited rates of revealed productivity growth that are absolutely comparable to what has been seen in manufacturing during the golden age of Factory Asia. In other words, it is important to look at the realities of performance at a disaggregated level before drawing strong conclusions about the development potential of particular sectors.

_____

References:

Bamber, P., O. Cattaneo, K. Fernandez-Stark, G. Gereffi, E. van der Marel, and B. Shepherd. 2017. Diversification through Servicification. Report prepared for the World Bank.

Costinot, A., D. Donaldson, and I. Komunjer. 2012. What Goods Do Countries Trade? A Quantitative Exploration of Ricardo’s Ideas. Review of Economic Studies 79:581–608.

Lemain, E., and G. Orefice. 2013. New Revealed Comparative Advantage Index: Dataset and Empirical Distribution. Working Paper 2013-20, CEPII.

Rodrik, D. 2016. Premature Deindustrialization. Journal of Economic Growth 21(1):1–33.

Shepherd, B. 2019. Productivity and Trade Growth in Services: How Services Helped Power Factory Asia. ADBI Working Paper 914. Tokyo: ADBI.

Comments are closed.