The most exciting part of my journey here at the Asian Development Bank Institute is that I get to meet inspiring leaders who have contributed immensely to helping solve the pressing challenges related to sustainable development. This time it was an interaction opportunity with the world-renowned “Mr. Toilet”, i.e., Mr. Jack Sim. If it were not for the efforts of Mr. Toilet and the World Toilet Organization (WTO), the United Nations would not have recognized 19 November as World Toilet Day, an effort by the global agency to mainstream the discussion on wastewater. The story of the WTO becoming a global movement and having remained so for the past 18 years is stirring, and it has a solution to offer for the global sanitation crisis.

There is a huge capital deficit for providing adequate water and sanitation services, a problem that Mr. Toilet wants to solve. An estimate from World Bank Group suggests that to achieve the water and sanitation targets of the Sustainable Development Goals, on a global scale, capital investment of about three times the current investment levels is necessary, i.e., $114 billion a year. Around 60% of the capital required is for improving basic sanitation and fecal sludge management. Furthermore, the sanitation problem is big not only in terms of its capital requirement. As per United Nations estimates from 2017, about 2.4 billion people in the world lack access to basic sanitation services such as toilets or latrines. About 862 million people still defecate in the open. Combined with safe water and good hygiene, improved sanitation could prevent around 842,000 deaths each year. The sanitation problem to this extent requires solutions that, once proven effective, can have a life of their own and can grow continuously.

“The taboo against sanitation is the root cause of inadequate investments in sanitation,” says Mr. Toilet. The taboo is that no one wants to talk about sanitation alone—sanitation has always been coupled with water. He stresses that the link between water and sanitation is quintessential, but the long-term benefits of sanitation improvement have fallen short in the eyes of policymakers against the immediately visible impacts of water improvements.

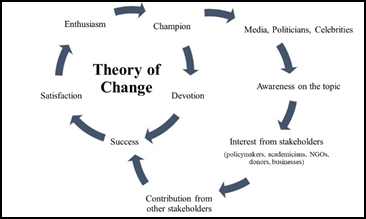

The success story of the WTO has a solution to offer on how to break the taboo against the sanitation challenge. The underlying systemic complexities, termed as the Theory of Change, when understood, can offer solutions that can be replicated elsewhere.

The story of the WTO began when one champion, in this case, Mr. Toilet, decided that it was time for him to no longer pursue the “Money Game” but that it was time to give back to society. He devoted his resources (money, time, and effort) to that cause and founded the Restroom Association of Singapore (RAS). The success of the RAS increased our champion’s enthusiasm and he marched ahead to make RAS grow. With the mission to make a better society, Mr. Toilet soon became determined to multiply the success of the RAS into a global movement.

Mr. Toilet was aware that his own abilities had limitations, and an obvious path for him was to inspire others to collaborate in the mission. Other collaborators could help the mission not only by contributing their resources but also by improving the productivity of the existing resources. The only challenge was that none of the other collaborators were really talking about the tabooed sanitation.

The other collaborators were important stakeholders in the sanitation spectrum. They included, among others, those from the media, politicians, policymakers, academics, celebrities, donors, those from nongovernment organizations, and the general public. Each of these stakeholders, working in their own self-interest, did not focus enough on sanitation. Hence, our champion needed a way to sync his agenda of sanitation with the self-interests of each of the stakeholders.

“When you become the joke, people laugh at you, but they listen to you.” This philosophy of humor, when utilized in the first World Toilet Summit in 2001 organized by the WTO, helped in gathering the attention of the world’s media. The summit went viral and, hence, provided world leaders an opportunity to reach the masses. Once the media started talking about sanitation, powerful politicians across the globe acknowledged the problem and offered their support to carry forward the movement. After the politicians came celebrities, turning the mission into a mechanism that had a life of its own. Acknowledgment of the sanitation problem itself created a space where the mission and its stakeholders (policymakers, donors, academicians, nongovernment organizations, business, etc.) could thrive because of the mutual benefits. Thus, “incentivizing the solutions instead of moralizing the problem” helped our champion to align the incentives of all the stakeholders and make the WTO and its efforts a global success.

Source: Author

The story of the WTO has lessons that are applicable elsewhere. As the Theory of Change suggests, the change begins with one champion with a mission. By incentivizing the solution, a single champion can help align the interests of all stakeholders and bring about the change the champion wishes to see. It is the role of all the stakeholders combined, and not anyone alone, that sustains the growth of the mission. Even the champion’s role is only to continuously fuel the mission by its resources and not to lead the whole movement. It is only when the champion and all other champions of the movement work selflessly, integrate their strengths, discover synergy, and incentivize mutual growth that the combined impact of the whole will be larger than the additions of all its parts.

Comments are closed.