For many years, cities have been the engines of economic growth in Asia. However, this growth has brought the immense challenge of the daily generation of millions of tons of solid waste, especially in mega cities. The amount of solid waste being generated in Asia is drastically increasing as 44 million people are being added to city populations every year (see ADB’s focus on urban development), and many cities are placing burdens on municipal as well as central governments. By 2050, 50% of the world’s population will live in the Asia and Pacific region (ADB, 2011).

Solid waste management is one of the most neglected areas of municipal services and infrastructure in Asia.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the world’s largest generator of municipal solid waste, producing almost 150 million tons of waste every year, with the figure rising at an annual rate of 8%–10% (ADB, 2009).

India has the second-largest population in the world after the PRC with 1.27 billion people, 17.6% of world’s total population. Of India’s population, 68% live in rural areas, while 32% live in urban areas. The urban population has been increasing day by day for the last few decades. India generates approximately 133,760 tons of solid waste per day, of which approximately 91,152 tons is collected and only around 25,884 tons is treated.

One of the reasons why solid waste management is neglected is the lack of budget at the municipal level. Also, in most countries, the private sector is not interested in engaging in solid waste management due to a lack of incentives and a low rate of return. In many municipalities in large Asian cities, more than 20% of the budget is allocated for waste management purposes.

In this article, we suggest practical funding schemes for incentivizing solid waste management and recycling projects for the private sector.

Credit guarantee schemes for providing fixed capital for waste management projects

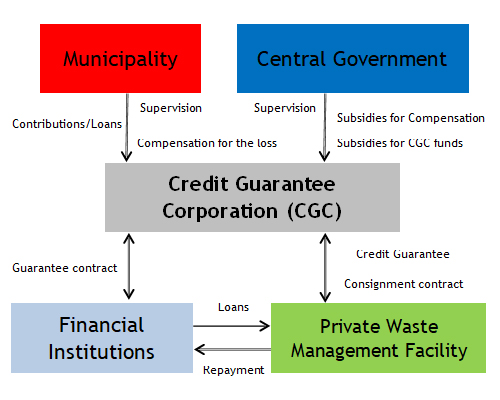

Credit guarantee schemes (CGSs) have been used in many countries and in various forms as a way of increasing the flow of funds to targeted sectors and segments of the economy, including small and medium-sized enterprises. A CGS makes lending more attractive by absorbing or sharing the risks associated with lending. A CGS can also increase the amount of funds lent to enterprises or projects beyond its own collateral limits because the guarantee is a form of collateral. It can assume the additional role of loan assessor and monitor and thereby improve the quality of lending. However, guarantee funds have a cost, which is borne by the fees charged and/or subsidized by the government or a third-party institution. A CGS normally consists of three parties: a borrower, a lender, and a guarantor. The borrower in the case shown in Figure 1 is a corporate or individual planning to establish a waste management project and seeking finance. The borrower typically approaches a bank or other financial institution for a loan. For reasons of information asymmetry, the loan request is frequently turned down. This is where the guarantor comes in. The guarantor is a credit guarantee corporation (CGC), usually run by a government or trade association that seeks to facilitate access to debt capital by providing lenders with the comfort of a guarantee for a substantial portion of the debt.

Figure 1 shows a proposal for a CGS for reducing the supply-demand gap for finance for waste management projects. This scheme is applicable especially for providing the fixed capital for projects (recycling, waste treatment, waste-to energy, etc.) that require large investment amounts. As illustrated in the figure, the proposed scheme is funded by the central government and the municipality.

Figure 1. Establishment of credit guarantee scheme for reducing the supply-demand gap for finance for waste management projects

Source: Authors’ compilation.

A CGS makes it easier for banks to lend to waste management projects because if the project defaults, the CGC will cover a large share of the lender’s losses. For example, if the guarantee ratio is 80%, if the project defaults, the bank can recover 80%. If there is no guarantee, the bank might not be able to recover any portion of the loan (Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2016).

Establishment of community-based funds for providing working capital for waste management projects

Experience shows that the major financing challenges faced by many waste management projects in developing Asia are difficulties in funding their working capital. Hence, sustainable funding solutions compatible with the socioeconomic environment of developing Asian economies are required.

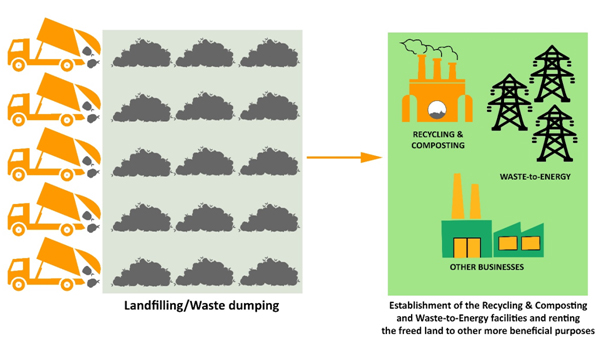

In developing Asia, landfills occupy large tracts of land, and the space in many large cities’ landfills is running out. By establishing recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy facilities, the freed landfills could be better used to support other more beneficial purposes, such as for generating rent, user charges, and revenue from selling electricity for municipalities or private investors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Allocation of landfills for alternative purposes

Source: Authors.

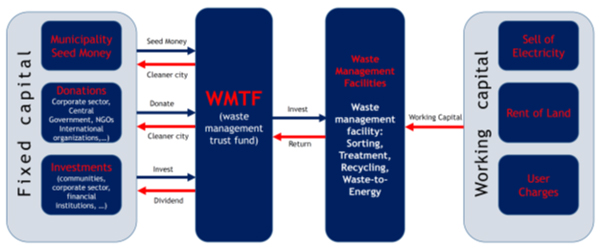

Figure 3 illustrates a waste management trust fund (WMTF), a form of community-based funding or hometown investment trust (HIT) fund for providing working capital for projects.

Figure 3. Establishment of community-based funds for waste management projects

Source: Authors.

In Japan, HIT funds are a new source of financing created to support risky sectors, such as solar and wind power. The basic objective of the HIT funds is to connect local investors with projects in their own locality where they have personal knowledge and interests. Individual investors choose their preferred projects and make investments via the internet. One of the major applications of HIT funds in Japan has been for wind power and solar power projects, and the funds have helped to raise money from individuals (around $100–$5,000 per investor) interested in promoting green energy. Through these funds, people can invest small amounts of money in the construction of wind power and solar power. The advertisement of each project on the internet plays an important role in pushing people to invest. Internet marketing companies provide a platform for investment and are able to market the projects. Local banks have also started to make use of the information provided by HIT funds. If the projects are carried out properly and are well received by individual investors, banks can then start to grant loans for projects. We believe that HIT funds are applicable to waste management projects and WMTFs can be a new type of HIT designed for waste management projects.

HIT funds have expanded from Japan to Cambodia, Viet Nam, Peru, and Mongolia. They are also attracting attention from the Government of Thailand and Malaysia’s central bank. Asia’s financial sector is still dominated by banks, and the venture capital market is generally not well developed. However, internet sales are gradually expanding and the use of alternative financing vehicles, such as HIT funds, will help risky sectors in Asia to grow (Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2017).

As Figure 3 shows, WMTFs can collect different forms of donations from the corporate sector, central governments, or international organizations; seed money from municipalities; and even investments from communities, the corporate sector, and financial institutions. The funds are project oriented and can be established for running waste management projects (sorting, treatment, recycling, waste-to energy, etc.). The investors receive dividends from the investment, and the donators and the municipality receive the benefits from the output of the waste management projects of a cleaner environment and hometown and social welfare. The working capital of the project can be funded by three sources: (i) rent of land (freed landfills); (ii) collection of user charges from waste generators (the facility is able to burn waste from other regions or other countries and receive the charges and fees—such schemes are operating in many European cities); and (iii) the sale of generated electricity.

Watch the related video.

_____

References:

ADB. 2009. ADB Supports Clean Waste-to-Energy Project in the PRC.

ADB. 2011. Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2011. Asian Development Bank: Manila

Yoshino, N., and F. Taghizadeh-Hesary. 2016. Optimal Credit Guarantee Ratio for Asia. ADBI Working Paper 586. Tokyo: ADBI.

Yoshino, N. and F. Taghizadeh–Hesary. 2017. Alternatives to Bank Finance: Role of Carbon Tax and Hometown Investment Trust Funds in Development of Green Energy Projects in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 761. Tokyo: ADBI.