In 2015, Central Asia made some important improvements in the environment for cross-border e-commerce: Kazakhstan’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) will boost commercial transparency, while the Kyrgyz Republic’s membership in the Eurasian Customs Union expands its consumer base.

Why e-commerce? Two reasons. First, e-commerce reduces the cost of distance. Central Asia is the highest trade cost region in the world: vast distances from major markets make finding buyers challenging, shipping goods slow, and export prices high. Second, e-commerce can help pull in populations that are traditionally under-represented in export markets such as women, small businesses and rural entrepreneurs.

Among Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) countries, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) stands out on e-commerce. In 2015, the PRC had an estimated 700 million net users, more than twice as many as the US and Japan combined. By 2018, it is expected to be the driver of global e-commerce flows. But how ready is the rest of CAREC to use e-commerce?

Business usage is low – even though infrastructure exists

For business to thrive online, access to high-speed broadband Internet is a must. In most CAREC countries broadband is available, and in some cases internet infrastructure has promoted strong growth in Internet usage by individuals in both urban and rural areas. Yet business usage underperforms relative to other regions in Asia.

Even though business usage underperforms, there are some serious efforts by the private sector to use e-commerce to drive growth. Kazakhstan’s www.chocolife.me is a B2C provider selling discount tickets to entertainment events, while the Kyrgyz e-commerce site www.prodsklad.kg is a B2B provider selling agricultural goods to restaurants and hotels. Payment in cash on delivery remains common because of limited reliance on credit cards and concerns about data privacy.

Cyber legislation is progressing at two speeds in the region

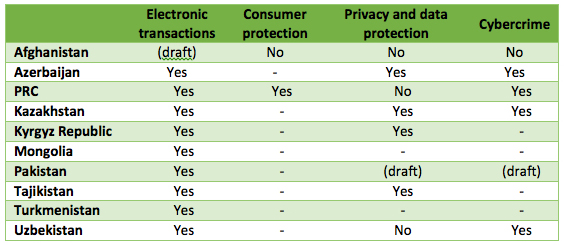

E-commerce needs a trusted regulatory framework in place to protect both buyers and sellers. Within CAREC, data show countries implementing facilitating legislation at different speeds.

The first group of countries—including Azerbaijan, PRC, Kazakhstan, and Pakistan—has complete legal coverage of cybercrime, and nearly all have data and privacy protection laws, with the PRC including consumer protection as well. The second group has laws in two or fewer areas. Of the four major legislative areas, all countries have at least a draft law on electronic transactions. There is, however, no evidence that any country in this group aside from the PRC has implemented consumer protection legislation.

Existing legislation in key areas of cyber laws

Source: UNCTAD 2015 (annex 3)

Note: – signifies “no data available”

Legislation is critical to building trust in countries where e-commerce is new. In Turkmenistan and the Kyrgyz Republic, government officials report that consumer trust remains low, which limits e-commerce growth. By contrast, in Azerbaijan e-commerce and public trust around it have grown since 2009. The passage of legislation on information safety and related issues was a critical driver of increasing consumer confidence. For Tajikistan, the WTO accession process has also been a promoter of the legal transparency that facilitates e-commerce.

Cross-border e-commerce targets neighbors

E-commerce within CAREC is largely domestic and urban, but increasingly, countries are putting in place structures needed to facilitate cross-border purchases. Many CAREC countries report targeting e-commerce efforts at their immediate neighbors. Afghanistan is looking toward India. Kazakhstan plans to use the Almaty-Bishkek Corridor Initiative (ABCI) to expand e-commerce with the Kyrgyz Republic. And the Kyrgyz Republic hopes that the ABCI can help leverage its Eurasian Economic Union membership as well as Kazakhstan’s accession to the WTO.

Accelerated parcel flows pose problems for customs

Cross-border e-commerce increases the frequency of small parcel flows, which is positive for trade volumes. But customs officials in Central Asia report three unexpected problems.

- Coping with the volume of flows. Customs officials in Uzbekistan and others have been overwhelmed by large inflows of small shipments using paper-based customs systems. Single-window facilities can address this problem. Azerbaijan has established a national single window; Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Uzbekistan are developing theirs; and Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are implementing UNCTAD’s ASYCUDA system to automate Customs.

- Uncertainty about how to estimate risk for small parcels. Increased import volumes also pose risk assessment problems, and how new global rules on antiterrorism and anti-money laundering should be applied to small parcel shipments is not always clear.

- Confusion about how to assess duties. When assessing customs duties based on the method of parcel delivery rather than the nature of the traded good, traditional postal services benefit from preferences enshrined in decades-old international agreements, while those delivered by express service providers do not.

What’s next?

CAREC countries are making progress toward enabling e-commerce. As automation improves, infrastructure spreads to rural areas, and as regional cooperation promotes cross-border exchanges, we can expect that the private sector will grow.

New areas of e-commerce are emerging that could be particularly well suited to the Central Asia environment. Online trade in livestock, for example, could meet the needs of rural traders. One example is www.farmia.co, which matches sellers with buyers in Serbia. Bringing traditional areas of commerce online also opens the door to job creation in support services like transport solutions and payments systems – all of which can help countries more intensively use the regional agreements that are rapidly coming online in the CAREC region.

This article was first published by ADB Development Blog.

Comments are closed.