Research has demonstrated that in general, training has a positive impact on an individual’s labor market performance: wages grow faster after training, training has positive impact on employment security, and training increases the probability of re-employment after job loss. A recent adult skills survey released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2013 re-emphasized that adult learning or continuing education and training (CET) can play an important role in the development and maintenance of key information skills and the acquisition of other knowledge and skills that are necessary for keeping pace with the changing work environment.

Factors and barriers to training participation

Who, then, goes for training? From the inclusive-growth point of view, it is ideal if vulnerable workers, e.g., workers with less than tertiary-level educational qualifications, have a higher incidence of CET. But much empirical evidence suggests that learning leads to learning—lifelong learning undertaken in the past has a strong and positive effect on the probability of an individual being a current learner, and high education levels are positively correlated to current learning or CET. Our own internal analysis using the recent 2013 OECD adult skills survey data shows that older individuals are less likely to participate in CET, and in most countries, higher CET participation is observed for those individuals with higher education. The data also shows that the top reason for non-participation for all OECD countries (except Poland) is being “too busy at work.” Other reasons for not being able to participate in training include: training was too expensive, lack of employer support, inconvenient training location, having child care or family responsibilities, and unexpected events that prevent an individual from engaging in CET. The UK Commission for Employment and Skills (2010: 10) noted that “the presence and absence of a culture of learning within the workplace also appears to play an important role in influencing both employer and employee decisions about investment in skills development.” If the prevalent barrier to participation is work related, that is, being “too busy at work,” and if a culture of learning within the workplace will facilitate the take up of CET, then, the work or employment must have a stake or be given mandatory responsibility toward CET.

Training funds from employers

One policy strategy that has caused employers to develop a vested interest in sending staff for training is the sectoral training fund (STF), as implemented in many European countries. Malaysia also has the same concept, a levy system called the Ministry of Human Resources Development Fund, which was set up in 1993, requiring certain categories of employers to pay a current levy of 1% of their monthly payroll into the fund, which the employers can use to claim reimbursement for training or training grants. The STF in Europe is a form of social partnership (by employers, trade unions, governments, and labour unions) where the partners are involved in the provision of and access to training through a sharing of costs and responsibilities. These funds are based on a compulsory or voluntary training levy as a percentage of the company’s payroll and can range from 0.1% to 2.5% depending on the country (Cedefop 2008). The levies collected from the employers are redistributed to them as grants or financial support for training (levy-grant mechanism), except in France where companies can use the mandatory training levy by either arranging and implementing the training programs themselves for their employees, or paying it to a sector-based organization called OPCA that will arrange the training for their employees (levy-exemption mechanism). STFs made the companies become more involved in training as levy collected is directly channeled back to companies for their use.

Cedefop (2008: 181, 184) summarizes the strong points and weaknesses of STFs as follows:

- Strong points:

- Strengthen social dialogue

- Increase company awareness of the importance of training and their commitment

- Increase resources available for training purposes (enterprise contributions, public funds)

- Mutualization and stabilization of financial resources for training

- Reduction of inter-enterprise training intensity differentials

- Promotion of SME participation in training activities

- Reduction of inequalities in access to training by employees

- Quantitative and qualitative improvement of training supply

- STFs as centers of expertise and sectoral knowledge

- Weaknesses

- Compulsory levies often seen by employers as additional tax burdens, drawback of competitiveness

- Not all enterprises get to benefit, SMEs in particular falling behind

- Insufficient attention and information for SMEs in some countries on the possibilities STF can offer

- Red-tape problems, “heavy” levy-grant administrative mechanisms

- “Deadweight” effects, especially for large-scale enterprises

- Risk of “dullness” in some STFs, drawing on captive resources

- Predominance of employer perspective on training needs, not employees

- Focus on sector specific needs versus transversal skills

Making training funds favors the vulnerable workers and unemployed

Considering these strengths and weaknesses, the Cedefop study offers a list of recommendations, such as improvements in funds administration, constantly ensuring effective cooperation among social partners, and improvement in information dissemination on the available training opportunities, etc. Also, despite the STF issues identified, Cedefop noted in their research that the sectoral training fund has been beneficial in favoring vulnerable workers.

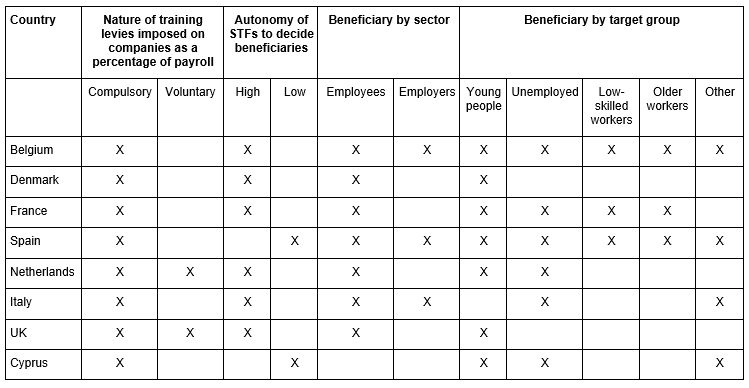

The table below shows the key characteristics of STFs in some European countries, as studied by Cedefop. For example, companies in all the countries have mandatory, i.e., legal obligations, to finance training, and Belgium, Spain, and France have beneficiaries that include key target groups, such as the low skilled, older workers, young people, the unemployed, and others. It would be worthwhile and interesting to study the intricacies of this policy strategy that make it effective or otherwise in targeting certain vulnerable groups, its applicability in Asia, and its role as part of the inclusive growth strategies of countries.

Table: Selected characteristics of skills training funds in some European countries

Source: Cedefop (2008).

_____

References:

European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop). 2008. Sectoral Training Funds in Europe. (retrieved 22 May 2014).

United Kingdom Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES). (2010). Praxis. An appetite for learning: Increasing employee demand for skills development. (retrieved 22 June 2014).