The story of East Asia’s rapid growth includes ample reference to the export of technologically complex manufactured goods, such as cars and computers. This is the model that has characterized Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Taipei,China. It also provides an example for Asia’s current middle-income countries, including the People’s Republic of China (PRC). They need to develop high-value manufacturing, the argument goes, churning out domestically designed goods or linking into global production networks. Failure to move up the value chain may result in a country getting stuck in the middle-income trap (Zhuang et al. 2012).

There is, however, a success story in Asia and the Pacific that has eschewed this path, building neither cars nor computers and instead relying on farm products and the services sector. With this strategy, it has gained a per capita income of $40,000, which is greater than that of the Republic of Korea or Hong Kong, China. The country is New Zealand and it may represent a model of development for Asian economies.

Economic development based on the agriculture and services sector

New Zealand’s services sector is the main driver of output, accounting for about 76% of gross domestic product (GDP). This is similar to many developed countries and encompasses a range of activities, none of which is particularly dominant.1 Industry, including manufactured foods and beverages, accounts for about 13% of GDP, whereas less processed farm, fish, and forestry products contribute the remaining 11%. Unlike developed East Asian economies, however, a large part of New Zealand’s export basket consists of processed agricultural goods.

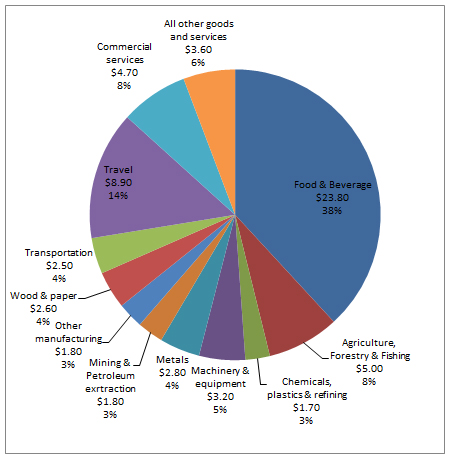

Food and beverages account for 56% of total merchandise exports by value, half of which is dairy products. If we consider total exports, which comprise goods and services, 38% is accounted for by food and beverages, 4% by wood and paper, and an additional 8% by other farm, fish, and forestry products (see figure). The latter category includes wool production from the country’s 30 million sheep. Lamb, mutton, and beef are also important exports. In sum, fully one half of total exports consist of agriculture-related products. Mining and petroleum extraction add another 3%.

Another 26% of exports are accounted for by services, notably travel (14%), along with transport and business services. The contribution of travel is directly related to the important tourism sector, which might be partly considered a primary activity because many tourists come to New Zealand for the natural scenery. Manufacturing that is not related to the agriculture sector does contribute to exports but at a much lower level. If we group together machinery and equipment; chemicals, plastics, and refining; and other types of manufacturing, they account for only about 15% of exports.

Figure 1: Exports of Goods and Services, 2013

Source: Government of New Zealand (2014)

High value agriculture products and quality control

New Zealand’s strengths are not just in raising animals and growing crops, however. These activities are supported by state-of-the-art processing to convert raw products into valued consumables. The largest dairy cooperative, Fonterra, which accounts for 85% of industry employment and earned NZ$20 billion in revenue in 2012, invested $376 million in new plants in 2013 alone to improve the processing of their dairy products (Coriolis Limited, 2013). Fonterra accounts for 50% of food and beverage exports and accounts for 70% of R&D in the sector. The dairy industry is clearly high tech and a world leader. The meat industry meets similar high standards. New Zealand produces a wide range of processed foods that range from infant formula and frozen meals to chocolates and pet food. A high technology approach is critical because many of its main markets, notably the PRC, are far away and require the latest in processing and packaging techniques to guard against spoilage and ensure freshness. In this way, the country’s export strategy is not easily replicable but is built upon both the capacity of agro-industry and the standards set by the government.

The industry seeks to keep abreast of the latest developments with 25% of firms in the food and beverage industry engaged in research and development and a full 54% involved in product or process innovation (Government of New Zealand 2014). For its part, the government’s Animal Products Act 1999 requires firms to register all exports of animal products intended for consumption, specifies foreign market requirements, and gives official assurance to overseas authorities of meeting those requirements. Other safety regulations cover non-animal primary products. These measures have ensured global consumer confidence. They have also allowed New Zealand producers to take advantage of problems in other countries; for example, when producers were able to rapidly increase infant formula exports to the PRC following the 2008 melamine crisis.

Along with investing in research and ensuring food safety standards, agro-businesses in New Zealand benefit from a supportive policy environment. Barriers to trade are very low – only 12 out of 119 countries in the world had a weighted average tariff rate that was lower than New Zealand’s 1.6% in 2010 (World Bank 2015).2 At the same time, bureaucratic regulation is kept to a minimum. New Zealand ranked second globally in terms of the overall ease of doing business in the 2015 Doing Business report (World Bank 2014). Red tape has been reduced or eliminated such that it takes only half of one day and one procedure to start a business. The country is ranked number one in the world in the ease of accessing business credit.

A growth model for emerging Asian economies?

With large agriculture sectors and good natural and historical sites, Asia’s emerging economies can also base their growth strategies on farming and services. However, just exporting raw products is not enough; they need to process them using advanced production techniques to maximize value added, ensure quality and improve food safety. New Zealand was able to become a market leader in dairy exports due to both its ability to produce sufficient quantities of milk to meet demand but to also invest in R&D to improve the value added and monitor its supply chain to ensure safety. For example, New Zealand was able to gain significant market share in infant formula to PRC, its main importer, due to its ability to keep its product free of impurities during the 2008 melamine crisis.

For Asian economies to replicate New Zealand’s success, producers need to meet these challenges of adding value to the products through R&D and with government support in the form of ensuring product and food safety standards. Harnessing the latest technology is critical for producing high value goods, even if those goods themselves are not very high-tech. A hassle-free environment for businesses, including startups, and an open and supportive trade regime are also key policy requirements.

_____

1 The services sector comprises 15 subsectors; the largest is professional services (at 8.1% of GDP) and the smallest is arts and recreational services at 1.6%. Other key subsectors include: Rental, hiring and property services (7.7%), health (7.2%), wholesale trade (6%), and construction (6%) (Government of New Zealand 2014).

2 2010 is the latest data available from this source. Many countries had the same rate (1.6%).

References:

Coriolis Limited. 2014. iFAB 2013 Dairy Review. Auckland, New Zealand

Government of New Zealand. 2014 The New Zealand Sectors Report 2014: An Analysis of the New Zealand Economy by Sector. Wellington: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

World Bank. 2014. Doing Business 2015: Going Beyond Efficiency. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2015. Data: Tariffs rate, applied, weighted mean, all goods (%), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TM.TAX.MRCH.WM.AR.ZS accessed 9 January.

Zhuang, J, P. Vandenberg and Y. Huang. 2012. Growing Beyond the Low-cost Advantage: How the People’s Republic of China can Avoid the Middle-Income Trap. Manila: Asian Development Bank

Photo: By Dave Young (“the dairy cow“). Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Looks like a good model for all economies aspiring for sustainability