Over five years after the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis, the EU financial system remains in a fragmented state. Banks do not lend to each other across borders without asking for a significant premium. In the larger eurozone countries, cross-border retail banking remains a negligible source of credit and thus could not compensate for the dysfunctional interbank market. As a result, in many European countries, credit for households and businesses—who mostly rely on banks rather than capital markets for financing—remains costly and limited, inhibiting opportunities for economic growth in the region.

Stalled integration

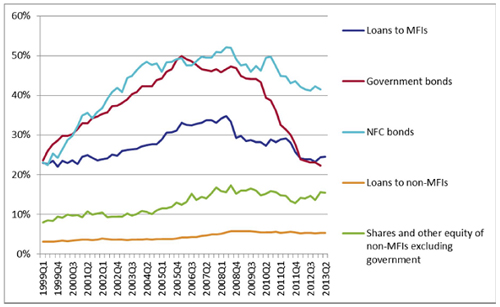

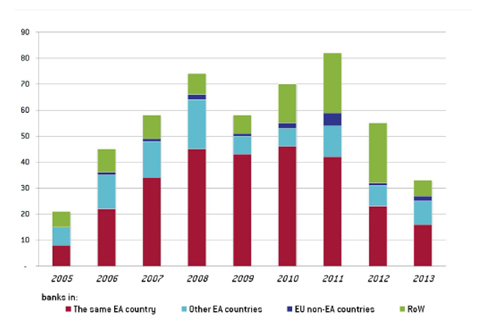

Prior to the crisis, the EU financial system was becoming increasingly integrated, particularly for countries in the eurozone. Unfortunately, the crisis undid financial integration in the interbank market, where cross-border integration had been most successful. In the eurozone, between 1999 and 2007, cross-border lending to eurozone monetary and financial institutions (MFIs) accounted for 33% of all eurozone loans, while cross-border lending for bonds of eurozone governments and eurozone corporations comprised 47% and 51% of the total, respectively. Since the onset of the crisis, these shares have fallen to 24% for MFIs, 22% for government bonds, and 41% for corporations. In contrast, cross-border lending to nonfinancial corporations, i.e., retail banking, always remained at a very low level throughout the Economic and Monetary Union (Figure 1). Reflecting this low degree of retail banking integration, the number of cross-border bank mergers and acquisitions is relatively low (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Cross-border Asset Holdings, Share in Total Assets

Note: The lines measure the share of the intra-euro area cross-border holdings in total euro-area holdings.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB date

NFC = non-financial corporate bonds, MFI = monetary and financial institutions include both deposit and non-deposit-taking institutions

Figure 2: Total Number of Euro Area (EA) Banks Bought by Banks by Region

Source: Sapir and Wolff 2013.

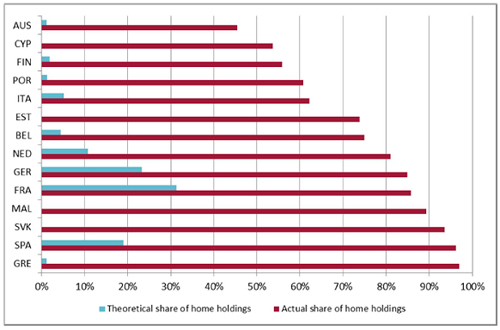

Other forms of financial intermediation in the eurozone remain underdeveloped. For example, ownership of listed companies is predominantly domestic and foreign ownership is significantly lower than what would be expected in a fully integrated market where investors would spread their portfolios across the entire eurozone (Figure 3). This home bias, in turn, negatively impacts investors: Since publicly-listed companies are primarily domestically-owned, the risks of holding shares in these companies are not shared and so any shock that reduces the value of shares in one country will constrain access to new financing for those within that country and will reduce the net worth of the citizens in the same country.

Overall, the state of financial integration in Europe is unsatisfactory, marked by a retail banking sector largely fragmented along national lines, bank mergers predominantly between institutions of the same country, and very different financing conditions in different countries.

Figure 3: Share of Domestic Equity in Eurozone Countries

Note: Theoretical share of home holdings is equal to the share of domestic market capitalisation of total euro-area stock market capitalisation.

Source: Bruegel based on World Bank data on stock market capitalisation and IMF CPIS data on cross-border holdings following the methodology of Balta and Delgado (2009).

The global financial crisis revealed three problems with Europe’s financial system (Sapir and Wolff 2013): The first is that cross-border financial intermediation happened largely through debt-based wholesale banking market integration. Better integrated equity markets would have allowed capital markets to absorb the massive shocks which the euro area was confronted with. The second problem is high exposure to risk relative to loss-absorbing capital and debt in the banking system, which translated into increasing demand for bailouts and numerous public assistance programs. The third problem is the contrast between the high degree of wholesale banking market integration that prevailed before the crisis and the absence of a European system for financial stability.

A reform agenda to end the fragmentation of financial markets, give households and corporations greater access to finance, and ensure financial stability in Europe should include the following elements (Sapir and Wolff 2013): First, the forthcoming Asset Quality Review by the newly-created Single Supervisory Mechanism in the European Central Bank should lead to banks that are viable to be recapitalized mostly from private sources, with public recapitalization being the exception rather than the norm. Second, a Single Resolution Mechanism capable of implementing sensible cross-border sales and mergers should be present to restructure non-viable banks. Third, greater attention should be given to developing a genuine cross-border bond and equity market in the EU to reduce reliance on bank funding and improve economic stability through better facilitation of risk sharing.

Bold policies needed

The European economy’s dependence on bank credit requires bold policies focused on solving the banking sector’s problems, the timing of which is paramount. As negotiations about measures to improve the European financial system continue, policymakers need to be aware that restructuring decisions today will undermine future financial stability if they are made without allowing for sensible cross-border mergers, and that such decisions will have to be accompanied by serious efforts to develop capital markets to ensure that the monetary union is sound in the medium term.

_____

References:

Sapir, A., and G. Wolff. 2013. The Neglected Side of Banking Union: Reshaping Europe’s Financial System. Note presented at the informal ECOFIN 14 September 2013. Vilnius.